Your podcast catcher not showing in links above (black circle with three dots)? Loads more on PodLink. Show is also on Spotify. and Google Podcasts.

Spokesmen Cycling Podcast

EPISODE 243: Cycling Palestine with Sohaib Samara, Malak Hasan & Julian Sayarer

Thursday 16th April 2020

SPONSOR: Jenson USA,

HOST: Carlton Reid

GUESTS:

Sohaib Samara and Malak Hasan, co-organisers of advocacy group Cycling Palestine.

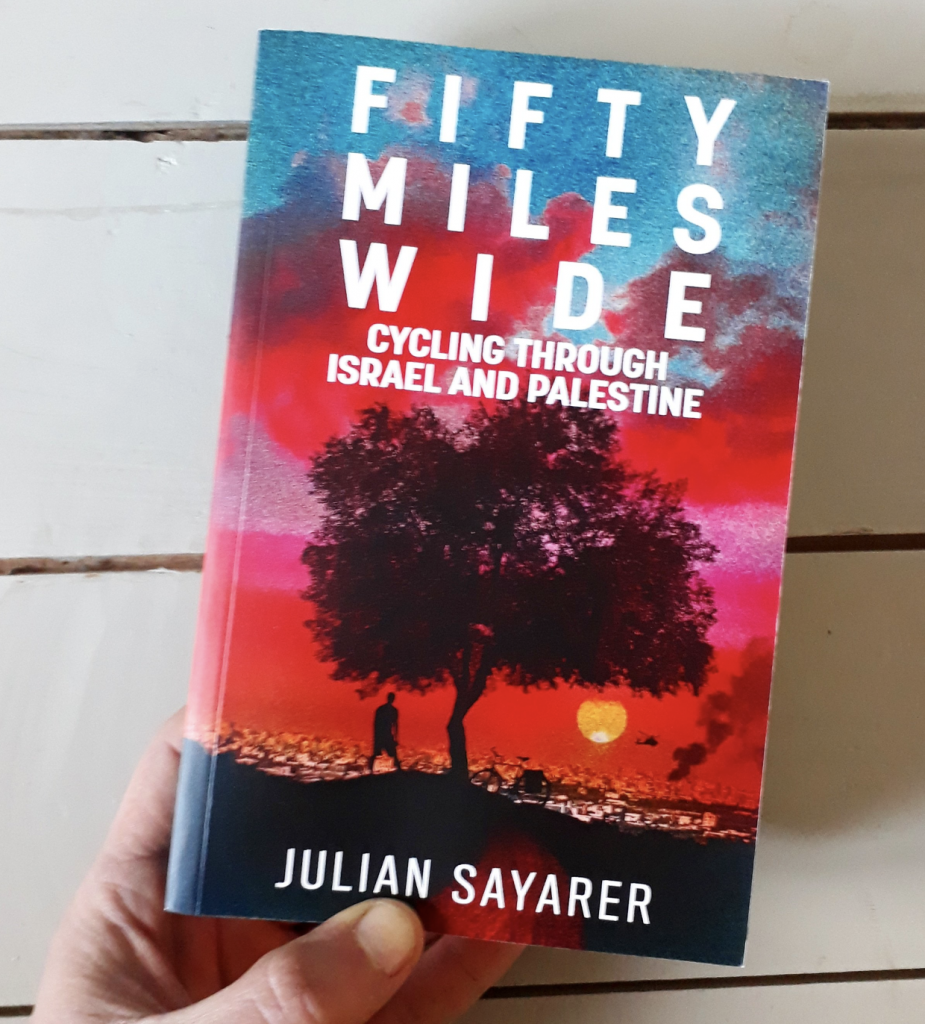

Travel writer and cycle tourist Julian Sayarer, author of “Fifty Miles Wide” a harrowing account of his recent cycling trips in Israel and Palestine, meeting with people on both sides of the divide.

TOPIC: Cycling in Palestine.

LINKS:

Guardian article “Why cycling in Palestine is an intensely political act.”

Forbes.com article on Bethlehem’s e-bike tour and Banksy’s Walled-off Hotel.

Cycling Palestine on Facebook.

Gino Bartali’s secret heroism; Ran Margaliot and Israel Cycling Academy.

Tout Terrain bicycles.

TRANSCRIPT:

Carlton Reid 0:13

Welcome to Episode 243 of the Spokesmen cycling podcast with me, Carlton Reid. This show was engineered on Thursday 16th of April 2020.

David Bernstein 0:24

The Spokesmen Cycling Roundtable podcast is brought to you by Jenson USA, where you’ll always find a great selection of products at amazing prices with unparalleled customer service. For more information, just go to Jensenusa.com/the spokesmen. Hey everybody, it’s David from the Fredcast cycling podcast at www.Fredcast.com. I’m one of the hosts and producers of the spokesmen cycling roundtable podcast. For show notes, links and all sorts of other information please visit our website at the-spokesmen.com. And now, here are the spokesmen.

Carlton Reid 1:25

Those sounds are from Nablus, Palestine. I was there before the lockdown, researching articles for Forbes.com and The Guardian. The Forbes article majored on a new e-bike tour of Bethlehem that zips past Banky’s Walled-Off Hotel, and the Guardian article explored Palestine’s burgeoning bicycle scene. For that piece I interviewed Sohaib Samara and Malak Hasan, co-organisers of advocacy group Cycling Palestine. We met in Bethlehem and the first part of today’s show is the audio from that interview, with Malak translating Sohaib’s Arabic as we went along. The second half of the show is also Palestine-themed — I talked with travel writer and cycle tourist Julian Sayarer. He has a brilliant new book out today. “Fifty Miles Wide” is his often harrowing account of a number of recent cycling trips in Israel and Palestine, meeting with people on both sides of the divide. It’s an unavoidably political book — heck, even Palestinian recipe books drip with political commentary; food is from the land, and this land is bitterly contested as it has been for thousands of years. So, this isn’t an episode for the faint-hearted — there are some graphic moments, in both halves of the show. Before that long discussion with Julian, which we did over the internet, here’s Malak and Sohaib who I recorded in the foyer of Bethlehem’s Manger Square Hotel.

Malak Hasan 3:14

Sohaib and I work together most of the time, but he’s the founder of the group. And he’s the one who he’s like the mastermind behind the planning of the, the trips, the all the logistics. So I’ll answer the questions that I know about the group as as a media expert, okay. I like the sound of the person who’s usually in charge of like talking about the group and if there’s a specific question they want to ask him, then I’ll just translate and talk about it.

Carlton Reid 3:49

So, when, what year?.

Malak Hasan 3:53

Well,

Malak Hasan 3:55

Cycling Palestine is the fruit of the passion of few Palestinian young men who love to cycle there was no access. There’s no opportunity it’s not easy to get cycling gear because it’s expensive oh you just call and get it and there are no shops here like there are no shops that he can just go and buy a bicycle. But they in a way had like this idea and they got maybe used bikes and they would go out cycle because they love it. They would explore Palestine go to these unfamiliar roads maybe with no with not really the greatest infrastructure but still they would do it and they loved it so much and they enjoy it so much to the point where they decided that you know, maybe we should invite other people to come try this out with us because it’s so fun.

Carlton Reid 4:53

And is this sorry, is this Ramallah This is all Ramallah? Ramallah?

Malak Hasan 4:57

Yes, it’s all Ramallah. and in 2016 it was Sohaib and two other friends, they decided to start posting on Facebook and invite people to join the tours. And it was as simple as you know, we’re going to maybe in a Mullah surrounding areas who wants to join, we have like two, you know, extra bikes, and then, you know, two people would join and then they were able to get another bike and, and so on, you know, until at some point there were like 10 people joining the, the trips, including myself, and that’s how I came to, to know so hype. And then we we we sat down and we were thinking, how can we like make this thing more organised? And we can grow this as a movement because we know a lot of people, when they see us, they’re like, Oh, my God, this is amazing when they join, but we don’t know how. And then we decided to start something called cycling Palestine. Something that will include all Palestine, there’s no borders, no restrictions, no roadblocks. It’s everywhere, even though it’s a normal and slowly we became you know, we started To leave Ramallah go to the, you know, Jordan Valley go to Bethlehem go to Holly in Annapolis just to get to know people finding out new roads. And and you know, after four years we have over 3000 members who join us. Yes, I mean, not at the same time, of course in each like tour, but you would see them like come and go depending on their schedules of work and know if they have time or not. And we have over, you know, 12,000 followers on Facebook of people who actually either joined either want to join or they are really invested in the idea.

Carlton Reid 6:32

So is this only leisure or the some people then start cycling and maybe think oh, I’ll cycle to work or so how do you think it it is?

Malak Hasan 6:47

Yeah, it has been shown and investigated which to any norm model and the best tomato FNS I should hire. Remember, it’s Like leisure in a sense of, I mean, of course we have fun, but we really look at, especially now that we grew, we also like we not only grew in size, but we also grew in mind, we realised that biking is not just like a sport, it’s a really a tool for change. And now we cycled to tell people that you know, environmentally, it’s good, socially, it’s amazing. And also like economically if you don’t have money, you can get a bike and you can go anywhere. It’s a it’s the best icebreaker for us whenever we are on the road someone wants to talk to us know who we are. So for us it’s you know, it’s leisure Of course especially in in circumstances where there is no a lot of like there’s there’s not many like outlets for Palestinians to you know, I don’t know like go to the beach or like have fun. So we’re like exploring the untouched areas, the roads, which usually we don’t usually go to to walk, you know, and so we cycle so for us now, a lot of people have adopted this as a lifestyle. They go to work on bikes. We have a lot of athletes who, you know, decided to become like professional cyclists with the minimum resources. I mean, you’re talking about bikes that are not like, you know, competitive or like professional bikes, but they want to become athletes. They cycled, you know, everyday to train with. In 2000. It had the struggle. In 2019, we actually the the cycling Federation became active, which is very late in the world of cycling. But that’s this was kind of a result to this leg growing phase that we’ve helped create. When they saw that more people are cycling more people are interested in this. So yeah.

Carlton Reid 8:45

In we’ve been in Jericho. Yeah. And there’s actually quite a few people cycling in Jericho for transport. Yeah, on electric bikes, mainly. Yeah. But in other places in Palestine, it’s maybe less because of the hill. Huh so what’s what’s the is Jericho is flat. Is that the reason why why does Jericho have more people riding?

Malak Hasan 9:07

Yeah. Is that like

Malak Hasan 9:09

between 50 and 100? Shakib? McIntyre Ah, good enough sorry. Yeah. So in truth carry on Qalqilya, which are two other governorates in Palestine they also have this like a cycling kind of phenomena. Like Jericho was also in Gaza. I’ve been to Gaza like few months ago for work, and they are Cycling is a big thing.

Carlton Reid 9:37

adults as well as children because children ride bikes, but is that the perception that it’s this is a children’s like, why are you doing a children’s activity?

Malak Hasan 9:47

So I think you know, here is where how I can explain this phenomena is that you cycle, not for leisure, but because you’re forced to in a way because it’s cheap. You can get a bike Put Like the bread and delivered Exactly. You don’t need the gas, you don’t need them, you know, fixing it is so easy. And also, you know, because of the fact that Jericho is flat makes it the ultimate really cheap alternative. But when you go to the other, you know, districts or the cities because it’s very hilly. No one is, you know, willing to go through that. But also, there’s a problem, you know, so heidemann, for example, found when he started Cycling is that the comments of the people were always like, they always told him, why are you cycling? You’re an old man. Now you should be thinking about like starting a family having babies, you know, working. This is stupid. Don’t do that. And so there’s this like, mixed like contradicting perception of cycling, but do you want me like you can only cycle if you’re poor and you need transportation and do delivery, but you cannot cycle if you’re an old man, and you should be working. You know what I mean? So if you

Carlton Reid 10:55

have a Mercedes or if you have a good car, you should not be on a bicycle.

Malak Hasan 10:59

Yes. I mean, you Obviously fooling around, and it’s to and even the girls like, I mean, it’s different. So for boys and girls, they start riding their bikes, you know, they get their first like small bike, you know, with, with the with the with the with the colours and everything. But you reach a point where as a girl, it’s no longer acceptable to be on a bike. That’s maybe a bit later for a man for a boy. But at some point, you have to be serious about studying about work about what you want to do in the future. That’s it.

Carlton Reid 11:26

So that one my next questions was going to be about this the status of bicycling with women. Yeah. And how different that is for compared to a man. So maybe it’s slightly more acceptable. It’s considered strange, but acceptable. Yeah. But for a woman. It’s strange and not acceptable. So how have you tackled that?

Malak Hasan 11:46

Yeah. So so maybe he can tell you first about his experience as a man because I think it’s it’s a bit of a misconception in our perception that men don’t have any troubles with cycling. They do. But it’s different than Great woman so maybe he can tell you keep sure what our climate tonight escalatory machaca Mr. meyen

Malak Hasan 12:05

[Arabic]

Malak Hasan 12:08

[Arabic]

Malak Hasan 12:10

[Arabic]

Malak Hasan 12:18

So he says,

Malak Hasan 12:20

basically the the comments, the main comments he always hears is like, Don’t you want to grow? You know, when are you going to grow up? Come on, you need to grow up, get a life. But recently since we’ve been doing this for over, you know, four years now people kind of lost openness. They’re like cause there’s no way they will change their mind they can, you know, be continued to cycle and they’re now accepting it more. As for me, I think the the challenges were way, way way more complicated because you’re not only doing something that is perceived as a as like as a game or like as as a toy or like as a way for kids to play. It was a way to break free from society’s you know, traditions, even religious misconception that it’s religiously unacceptable or forbidden. So, because I’m visibly Muslim so when I’m always on the bike people are always throwing comments in my face and how could you be a good Muslim and also like be showcasing yourself or like exhibiting your body on the roads. For example, the my friends, my cyclists, friends, the men would be more it would be easier for them to embark on these amazing challenges and adventures. Because no one will be asking where this man is sleeping. Where is he going? Is he alone? Is he going to be fine but for me because most of the men, the cyclists that are men, us the women the small number will not be able to have the same freedom to join their their adventures like doc trip. We went off copy we were nine Guys and two girls. And when we came back most of the comments were like How could you be sleeping like intense and on the roads deserted road with like nine other men? So I think it’s a combination of religious Of course it’s not like accurate no foundation for it because it’s traditional. It’s, I think social, like expectations of a woman to be at home take care of the babies be decent and modest. And it’s a kind of, in a way in their mind, it contradicts with being a cyclist as well.

Carlton Reid 14:32

So that’s the Muslim point of view. Yeah. Do you have Christians is this like, you doesn’t matter who you are? what religion you are. It’s the bicycle. That is the mix. There’s the thing that keeps you together, or is that song for some sort of segregation here on religious lines?

Malak Hasan 14:57

Should I know

Malak Hasan 15:02

Well, Yanni, what they said exactly like I think I tell you a story. And so you will be able to understand that at the end of the day, it’s not religion as much as society, Christian Muslim, even like Jewish, if you live in a society you will adopt the same ideas. For example, the other day I was shopping for like a new apartment from my my friend, she colleague, she came here to palisade from Germany, we were looking for a new apartment for her. And the guy who was renting he’s a Christian. And so we got to talk. And his daughter was there and I told him about my cycling, you know, work with my friends. And the girl she hooked me and she was like, please send my father that I want to you know, ride a bike, he wouldn’t let me and then I was like, what I mean, you you you’ve been like telling me about how amazing my work is. He works with this like NGO. You’ve been telling me about how amazing my work is a cycling and then you won’t let your daughter cycle and he was like, Yeah, because I don’t want society to attack her. I was like, but doesn’t matter if we continue to listen to society. You, nothing will change. And that was actually very recent that I thought it doesn’t really matter. You know, what is your religion? What is your background, if you live in a society, you want to confirm, you want to be a part of them and you want to avoid being attacked. And this is what makes the difference between someone who wants to make a movement or like, create a movement or someone who just wants to follow the lines, you know,

Carlton Reid 16:22

to all back Christians in your group.

Malak Hasan 16:25

Yes, yes. So,

Malak Hasan 16:26

there’s no it’s just it’s just the cultural barriers, not religious barriers.

Malak Hasan 16:31

No, no, no, definitely, I think in Palestine. And I think they both agree that in Palestine, religion has never been a dividing force. I know there are the cases here and there. But I can definitely tell you that I would never come to you in the street and ask you what is your religion? I’ve worked with colleagues for years before like realising that they come from like a different like sect or religion like it’s not like in other parts of the Arab world like in say, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq. It’s never been I’m like a defining factor in our relationships. But of course, there are like these exceptions here and there.

Carlton Reid 17:06

So put that another way, does it actually help bring people together from different cultures, different religions? Because you are joining with something that is an overarching thing and you are coming together to share something together. And does that bring you together? More than if you just met in some other way?

Malak Hasan 17:31

[Arabic]

Malak Hasan 17:40

[Arabic]

Carlton Reid 17:46

me

Malak Hasan 17:49

when I want to talk about differences, religion does not come to my mind as maybe something that cycling has helped, like bring together in our case. Maybe because you know, in Palestine we have Christians and Muslims it’s never been an issue. And we never really asked anyone in our groups if they’re like Krishna we don’t even know like it’s never been something that we talk about. But I think when when we’re talking about like bringing people together, I have other maybe considerations. So we help as I told you like, we helped bring the breadwinner who lives in a tent with the with the with the sheep and has a different lifestyle, different even accent. So as maybe somewhere on Facebook, or maybe a service industry decided to join us. And now they’re cycling with a person who studied in their like a fancy school, in Ramallah. In my case, someone who started in an unknown school in a village. We also had the refugees come, I think we also had the religious conservative, join us and also mingle with someone who is very liberal, have these like even conversations along the way, and then you will see that this religious or conservative person is no longer having an issue with me as A woman being on a bike, you would see that eventually we’ll be also talking on Facebook if someone tried to attack me who would defend me as a, as a, as a human, because he knows who’s black is. He knows that he’s my he’s my friend now, regardless of what religion in his mind says. So I think yes, that’s and this is why we do this for four years, you know, has been doing that. And I’ve been doing this for four years, cycling has been really the most effective social tool, you know, for change. Because as I told it’s an icebreaker, people are really intrigued when they see us, they want to know what the hell we’re doing. And they just want to be part of this. And so I think we have leverage with Viking that we are thinking when we think about the future, we believe in that it’s going to be a major, a major turning point for Palestinians if we continue to use cycling to to bring change, you know what I mean?

Carlton Reid 19:54

So we’ve talked about the complications of culture, religion,

Carlton Reid 19:59

yeah, sex.

Carlton Reid 20:00

Yeah, add in the complication of where you live. Yeah. So you are under occupation. And you cannot go everywhere you’d maybe want to go because of the ABC situation. So. So how does how does that complicate things on top of all those other complications?

Malak Hasan 20:21

I think Sohaib would be the best person to answer this question because he’s had amazing stories encounters and problems with that in that regard. So I’ll just translate by luck and he can … [Arabic]

Malak Hasan 20:46

So just for context, he’s a paramedic. As a job. He tells me a story to try to answer a question of how difficult it is to do anything, I think, I think in Palestine But mostly to be like a cyclist. Because you as you know, a cycling you have to go on roads and most of the good roads are the settler roads we call them the ones by Israel which means they’re under like heavy Israeli control there are patrols on the road. And so he tells me a story to kind of to give you some kind of sense into how how difficult and dangerous sometimes it could be. He was with his friends with his friends without when they started cycling and so they were taking this bypass road into like a main. We call them separate roads because it’s they’re usually used by the settlers in the West Bank. And then they were stopped or pulled over by by a patrol and next to a gas station. They were asking them who you are and what you’re doing here. And so when they realised they were Palestinian because most of the time we mistake as as foreigners because there are not a lot of Palestinians who cycle they took them behind the gas station. They asked him to take over in the details of their vests. And to take off their helmets they took them aside with the with the with the bikes. And because so hype speaks some Hebrew he heard them say if they should shoot them in the foot or maybe in the arm like they were like taunting them in a way. And that was in a time where there were a lot of stabbing kinds of incidents against Israelis was a very tense period. And I asked him if you were afraid, he was like, I was not really afraid for myself because then a day if I’m gonna die that said, I’m gonna die I could die anywhere. But he was very worried that if this escalates in a way if he tries to defend himself or like to tell them like there are no grounds for you stopping me and treating me like that, they could easily shoot him treat him in a different way like arrest him and if they eventually killed him for example, they can say that he was posing you know, danger to them and then eventually they will blow up his family’s house. And, and you can see like how you’re brain starts like to go No wonder in dark places while you really just want to go cycling. And for me this is also the same Jani the other day, we were going to the another Jordan Valley on a bike actually it was last Friday. We were also like interrogated on the road by the Israeli soldiers. Even though we were not doing really anything, we’re just waiting on the side of the road for the rest of the group to join us. And so they came. And what I always say to people, that I have no problem being nice to anyone. But sometimes it feels a bit difficult to be nice to someone who’s not treating you in a nice way. But you feel like you have no other option but to say thank you to someone who’s occupying you. Thank you for someone who’s just taking your idea for no reason someone was even not willing to tell you have a good day when you told them like Have a good day because you’re always worried about what’s going to happen if I tick them off the wrong way. You know what I mean? So we’ve always been pulled over Israeli soldiers sometimes even the checkpoints we cannot just cross we arrived in a place where there’s a checkpoint and we have to go back so it seems like there’s always it’s never been free will will never be free but we always try to see the good side in it at least we are trying to do something nice

Carlton Reid 24:18

so difficult question yeah. Could Israelis be a part? I mean is Israeli soldiers doing their job they’re stopping you that’s not good. That’s not nice. But could an ordinary Israeli could they join cycling Palestine? Would they want to join psycho Palestine? How do you think they think about Palestine? Yeah.

Malak Hasan 24:43

[Arabic]

Malak Hasan 24:45

[Arabic]

Malak Hasan 25:00

So I’ll give you his opinion. And then also like explain more from my side. He tries to sums it up in few words, every Israeli is was will be a soldier at some point. And we cannot judge anyone. But if they did not do anything bad to me now, they might do something bad to someone else without any grounds. And it makes it difficult to have faith and trust in in someone when you know that they’re kind of what is the word they are part of occupation. They’re standing still not doing anything approving something that is as bad as that. And so this stands of a moral dilemma for us in how we even we know that they’re amazing Israelis beautiful, doing amazing things to humanity. I cannot say you know, that every Israeli is bad. Like I can’t say that every Palestinian is good. But it makes it difficult for me as a Palestinian, as both, you know, to Palestinian educated, open minded, peace loving Palestinians to accept Israelis when we don’t know for sure that there are also against, you know, crimes against humanity. They are not against injustice, they’re not against like occupation killing innocent people, blockading people in Gaza. So it makes it difficult for me. And regarding other question about, well, they want to join I don’t think most of them will want to join either because they don’t you know, because they have political reasons, of course, or because the Israeli government is doing great work in like increasing propaganda against Palestinians, you know, creating this idea of the other who is like we’re just waiting for the SEC the right moment to shoot you and kill you. I mean, you’ve seen on the way all these like way Like billboards or like red signs that says, you know, it’s dangerous to go into these areas? Well, I know many Israelis and I have Israeli friends and I even know it like Israeli journalists who come and go every single day. Unless if you want to go there and provoking people, you might be hurt, of course, because it’s a very tense, you know, reality. But other than that, it’s not like the zombies are living on the other side. You know what I mean? I think, what I always see these like red signs, I’m like, yeah, it’s as if there are the zombies living on the other side, and they’re like warning them from the other. And so your question has many layers, but I think for now,

Malak Hasan 27:40

it’s not

Malak Hasan 27:43

in line with our maybe side of the story of like narrative, to welcome Israelis unless those are explicitly saying that we are against occupation. We’re not going to live in a in a village. That was destroyed in 1948 when maybe my father My grandfather was living there, someone who is like I know a lot of Israelis who refuse to come to Israel, because they’re like, unless there is no just solution for Palestinians, we cannot be part of this. So I think it really, it was really the electorate depends on the case.

Carlton Reid 28:17

Do you think if I came out here as an independent cycle terrorist, I would be welcomed the same way I was welcomed in the 1980s.

Malak Hasan 28:27

Even more, even more, okay,

Malak Hasan 28:29

I mean, Sohaib, and just to translate and keep lohaib in the conversation [Arabic]

Malak Hasan 28:44

And also that if you were able to send a really great message when you came cycling, like way back, you had an impact in a way and if you come again, and people always like, welcome someone who is willing to say things the way they Are and also support their rights to just live a decent life. So Palestinians I think even though we have like poverty, we have a lot of, you know, social problems, but we are very educated and we have come to understand the power of international support and solidarity. So if you walk into the West Bank, I swear you can get you’re going to be like, maybe too overwhelmed with, with with the respect and with with the, with the with the support and people wanting to have you in their homes because people have realised that any person who comes to Palestine will maybe be a better voice in Sending out a message because no one trusts us any more. Like even if I want to say to any delegation or anyone that we are under occupation will be like, yeah, you say that, but if someone from outside comes in, sees what’s been happening and sends out a message will be heard better. It’ll be more credible in a way from coming from a white man, like a journalist is like, no. So yeah, I mean, people understand A bet and they will welcome you even more.

Carlton Reid 30:02

Okay, yeah, you, me so you had a background in Swansea, which you that’s where you found cycling. So tell me about what you’re doing in Swan z and how you are riding out to the coast and that’s how you fell in love with cycling. I’ve done some research.

Malak Hasan 30:19

Yeah, yeah, obviously, [Arabic]

Malak Hasan 30:30

yeah. Well, I mean, my story is, I think I’ve told the story before but in a nutshell. I’ve always loved sports. I was born in the UAE did a lot of sports, karate, no dance floor, swimming, but then came back here. It was, of course, a very tense situation after the you know, Intifada. There were roadblocks, curfews. So was kind of denied this opportunity to continue with my sports life and Thankfully, because of my line of work, I was journalists, you know, I speak English. So I had a lot of opportunities to travel. And everywhere I go, I would just always get a bike and cycle so I kind of kept my love for biking abroad. But when I went to Swansea, the first thing I did was buy a bike a square, like I went to this used bike shop and it was like, I need a bike. I don’t care what kind of bike remember, it was like black and green. And he called my, you know, then fiance now my husband and I told him I got a bike. It’s like 70 pounds, you know? And he was like, well, that’s great, you know, and they started right. My husband Yeah, yeah, No, he doesn’t. Okay, he doesn’t right now. I mean, I took him to Jordan wants to try biking in like a safe environment because he is convinced this is not safe here. And then he was like, No, this is not for me, but he’s very supportive. Yeah, anyway, so yeah, I kept biking and I swore I would bike like hours every day and then just felt so free, because I would like feel so overwhelmed. Well, Studying in everything and then get on a bike and feel very relaxed. And then when I came back here I wanted to go back to biking but I was so terrified of people like attacking me all the time. And they stopped biking for a long time, you know, maybe for six, maybe even nine months, until I found so hype at the time that that’s taking back to the slick elite bikers like professionals in Palestine when you try to join this like biking community, it’s very exclusive because Who are you to join us on this amazing adventure? When you have no background in mountain biking? Like no one was welcoming enough of me as a woman. I have no background. I have no equipments, no bikes what I’m gonna do, and so also rejected or even ignored by those who I contacted, but then I contacted so I was like, Yeah, please come and we met each other, went on a bike and never stopped again. It’s amazing

Carlton Reid 32:56

that you’re doing journalism in Swansea?.

Malak Hasan 33:00

Media practice and PR. Yes.

Carlton Reid 33:02

Okay, it’s a long way when what year was that?

Malak Hasan 33:04

was in 2013 14

Carlton Reid 33:07

Okay, and then what are you doing now here

Malak Hasan 33:10

I worked as a freelance journalist for a long time, Al Jazeera their weekly in London that some you know work for the forwards in the US I’ve been doing a lot of stuff but then I I realised that I can just possibly like focus too much on like freelancing because I mean you know, media is very difficult you have to be always on the run it’s not enough money. So I decided that if I want to like dedicate my life also for sports, I need to find a better job so I found like an NGO but paying you know, job and you have to kind of, I think in Palestine, everyone has to sacrifice a part of themselves. Because I’m an economy’s economy’s bad and everything is bad, but I, I just love that we are biking together, and I feel like I’m doing something even if it’s not like journalism, which I absolutely love.

Carlton Reid 33:55

Yeah, so clearly there are some places as possible. Indian you can’t go in your homeland so where can you I guess the settler communities you can’t go yeah but other like you know trails which you would absolutely love to go but it’s maybe too dangerous for you to go or you can you can do parts of it but not the whole of it what’s Where can you not go and where would you like to go

Malak Hasan 34:23

okay so aside because he’s experts in trails, but as I like to [Arabic]

Malak Hasan 34:33

[Arabic]

Malak Hasan 34:34

[Arabic]

Malak Hasan 34:38

Yep. So he says that he of course would love to go all over the West Bank but the problem and if you’re familiar with the map, you can see it’s basically like a, you know, like Swiss cheese at the moment. So, between Every valley and another Valley, there’s a settlement. If you want to like Hi, let’s say cycle for I don’t know 15 kilometres, you will be faced with at least two checkpoints and settlement maybe another like surveillance tower patrols. So in a way there’s the continuities always broken for a sport that is based on long you know distances and and space, which has always been a problem for us because so for them as the guys who are into mountain biking usually what they do is they do special, very exclusive trips because it’s not safe but they will still would love to do it. So maybe they will go into this like forced, you know, forced area cycle. It’s a settler, you know, maybe trail usually Israelis or their soldiers, they would do it try to disguise themselves as maybe foreigners, but they don’t do that much because it’s not safe and they would not never take other Palestinians and be responsible for their safety. So for example, I’ve never been on these like, special like mountain trails because it’s just not that safe. He sometimes goes on When he really needs that like, like, you know, rush, you know biking rush. But as as he mentioned, this has been a problem. And so that’s why we’re always confined in the roads between villages. Or in worse worst case scenarios, we hit the main roads, the settler roads, but these are usually just for a small portion of the road to be able to arrive into the other village on the other side.

Malak Hasan 36:25

Yeah. Okay. Yeah.

Carlton Reid 36:27

Thank you very much for coming here. And then talking to me.

Malak Hasan 36:34

It’s a pleasure. It’s been fantastic. Thank you.

Malak Hasan 36:35

Yeah, really good. We would have loved to actually have you with us. You know, bike. I wish if you if you stayed longer, we would have liked taking you to this really nice trails called the [Sugar Trail]. The Sugar trail in the Jordan Valley area, you know, it’s a beautiful trail. I think you will appreciate it.

Carlton Reid 36:55

Mybe sometime after lockdown ends I’ll get back out to Palestine — I’d love to ride the Sugar Trail, maybe on a gravel bike. Thanks to Malak and Sohaib there, and sorry for the background noise but it was a busy hotel foyer, you know, when hotels used to be open. Anyway, because we’re still on lockdown and people maybe have more time than usual to listen to podcasts this episode is a long one. But before I play the audio with round the world adventurer Julian Sayarer here’s my co-host David with a commercial interlude.

David Bernstein 37:39

Hey Carlton, thanks so much. And it’s it’s always my pleasure to talk about our advertiser. This is a longtime loyal advertiser. You all know who I’m talking about? It’s Jenson USA at Jensonusa.com/thespokesmen. I’ve been telling you for years now years that Jensen is the place where you can get a great rates, selection of every kind of product that you need for your cycling lifestyle at amazing prices and what really sets them apart. Because of course, there’s lots of online retailers out there. But what really sets them apart is their unbelievable support. When you call and you’ve got a question about something, you’ll end up talking to one of their gear advisors and these are cyclists. I’ve been there I’ve seen it. These are folks who who ride their bikes to and from work. These are folks who ride at lunch who go out on group rides after work because they just enjoy cycling so much. And and so you know that when you call, you’ll be talking to somebody who has knowledge of the products that you’re calling about. If you’re looking for a new bike, whether it’s a mountain bike, a road bike, a gravel bike, a fat bike, what are you looking for? Go ahead and check them out. Jenson USA, they are the place where you will find everything you need for your cycling lifestyle. It’s Jensonusa.com/thespokesmen. We thank them so much for their support and we thank you for supporting Jenson USA. All right, Carlton, let’s get back to the show.

Carlton Reid 39:05

Thanks David and we’re back with a distinctly Palestinian flavoured episode of the Spokesmen Cycling podcast. And before I get complaints about partisanship — my Guardian article featuring Sohaiub and Malak got me labelled with some pretty hateful stuff on Israeli news sites — those wishing to complain may want to check on this show’s back catalogue. We’ve had episodes about the Giro d’Italia start in Israel, with David and myself recording audio from Jaffa and Jerusalem, and search out the episode with Israeli Ran Margaliot, a former pro cyclist and co-founder of Israel Cycling Academy and Israel’s Bartali Youth Leadership School. Anyway, let’s get on with today’s extended episode. Next up is Julian Sayrayer, author of “Fifty Miles Wide”, out today.

Carlton Reid 40:04

Julian, I have read your book. It is a fabulous book. I’m going to ask first of all, because I’m a writer, and in fact, we’re both. We’re both published authors on Israel, in fact, right. So that’s a bit of a strange one unique thing for us to be talking about. But first of all, I’d like to ask that there’s so much detail in the book. So I’m asking as a writer, how did you get is it from memory? Were you taking really copious notes? We’re taking photographs, and then you know, using that to describe, like, you were describing things like, you know, there’s a thistle of a certain colour in a certain part of, you know, a muddy road, and it’s just incredibly detailed. So how are you physically researching this when you’re there? On the ground?

Julian Sayrayer 41:01

It’s a good question I get asked that a lot. And I think I must just have been somewhat a little bit blessed as a travel writer to get a good memory. I mean, I take notes, written notes, which I think is also good for the memory to actually like write in a in paper with pen. I take a few photos by and large, and they don’t generally the things I’ve photographed, for the most part, haven’t much appeared in the book. I mean, the festival you talk about is very common at the roadsides of Palestine. And I remember the first time I was there, noticing just how vibrantly blue it was. And actually again, it’s funny that you pick that out because I do have one I pressed in one of my notepad, I have the pressed version of it somewhere. And so yeah, and I again, I just think that was a particularly vivid imprinting thing I think I saw the first one. I was like, Wow, what a beautiful colour. And then a few days later, I must have passed hundreds of them. So I think that that in particular is is one of the most common common Types of floor at the roadside. And other than that, yeah, I think I just must have a fairly good memory, it doesn’t feel quite as sharp as it used to. And things like dialogue, I find myself jotting down notes as people are speaking a little bit more than I did. But yeah, just

Carlton Reid 42:17

as my next question, because dialogue, clearly, you’ve got to get absolutely spot on, especially when you’re interviewing people, who will we’ll get on to and when we were in Cannes talking, you know, very, very prominent people in the Israeli peace process.

Carlton Reid 42:32

So are you recording them? Or you’re always doing notes

Julian Sayrayer 42:35

a couple of times. I’ve recorded I spoke with hip hop act in Ramallah, Harry, you know, as musicians were fairly used to the idea of an interview being recorded. And usually the negotiator I spoke with wouldn’t have been recorded. They were conversations over a while and I probably would have gone off after we’ve spoken and written down immediately, and paper and pen what was said, and then there’s He say because he’s quite a sensitive figure, institutional figure, and to some extent within Israeli negotiations over the decades. And so that’s one of the interviews where he got sign off, and which he hadn’t asked for in advance, but just as a courtesy to him in his, his standing, I am, I will show to, to, to be absolutely certain that he approved what was going out in his name. And he was I mean, obviously, I think in travel writing, and especially when you’ve got a political dynamic, you’re obviously doing nobody any favours unless you’re recording the Absolute Truth. I mean, it should sort of go without saying, but I guess in something like Israel and Palestine, so many parties to to greater or lesser extent, legitimately come to the table with a pre existing agenda. And I understand the reasons for that, but I think in terms of just recording with with absolute accuracy, people’s views and what you see is kind of a service in itself. Hmm.

Carlton Reid 44:06

So my book written many, many years ago in the 1990s, in fact, was a guidebook was the Berlitz guidebook to Israel, which I wrote straight after my university degree which actually in religious studies, which was handy. And that was a book that even though it was a general guide book, and it had nothing to do with bicycles whatsoever, I did the research for that book from the saddle of a bicycle, which is a good way of going into your book because it’s really such a small country. You can and Palestine is a small part of that part of the world. There is it’s easy to get basically if you’re a fit cyclist you can get to the from the from Alaska In the south, up to Haifa, and north in a day if you if you if you’re pretty fit. So your book is called 50 miles wide, which is basically alluding to that, that, that that smallness of this this part of the world that is actually massive in the news yet is tiny on the ground.

Julian Sayrayer 45:21

Yeah, absolutely.

Julian Sayrayer 45:24

It’s funny, we have another commonality there. And my first job out of university was also with berlitz, but as an English teacher in Istanbul.

Julian Sayrayer 45:32

So

Julian Sayrayer 45:34

But yeah, I mean, the bicycle as always, really is an amazing, it’s an amazing way to see anywhere I find. And especially a place that is the nature of the politics, the conflict, whatever we call it, the dispute is so rooted in the land. And the bicycle is such an impressive way of seeing that land, especially when it’s kind of beset with checks. points and rays of what I have. And obviously the the wall that Israel constructed to separate itself from Palestine and which divides, you know, Palestinian villages from their farmland and all kinds of things. The immediacy of the landscape in that way, I think, is is apparent in no ways more than than when you’re on a bicycle. And, and yeah, 50 miles wide, is it the title, I think when I was looking maps prior to my first visit, and realising literally how easy it was, sure, comparatively, it would be to cover the distances and you know, certainly the West Bank, and parts of it up towards Golan a very hilly So I think those those 50 miles as the crow flies can sort of like concertina out into sort of longer distances. But yeah, it’s very small. And I think that that kind of is reflected to an extent In the politics, if you kind of imagine something like a pressure cooker, which is maybe an unfortunate example, in some ways, but you know, villages and particularly Israeli settlements in in the occupied territories are all so close together. There is, in lots of ways very little space, even geographically for the tension and the trauma that accumulates with the attacks that go on or whatever. The space or the lack of space allows very, very little room for the buildup of tension to dissipate. So yeah, I think it’s a really massive part of it. And I do think from an external point of view, it’s kind of why geography and in some ways our lack of familiarity with the Middle East and the terrain of it becomes a problem in understanding these conflicts and its politics from the outside because it is, I mean, even me, I’m half Turkish, I know my mother hitchhikes around Israel in the 60s, I’d like to think that I, I know the Middle East to some fair degree, but still 50 miles wide when I first noticed that it’s Yeah, as you say, it’s it’s kind of striking. And then I think on some levels, it’s hard to understand an area in politics if you don’t understand its geography if you don’t necessarily understand even how it’s mapped reads. And then, as you mentioned, this the Middle East as a whole is an absolutely vast section of land. And often the the way that we reduce it down to very simple elements, whether that’s Israel, Palestine, Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, you know, these countries are larger and more spread apart spread apart than Poland, Austria, Russia, UK, France, and it will seldom be expected for people to have a particularly insightful and the knowledge of the politics of all of these, all of so many European countries. Say, and yeah in the Middle East as often a sense that, you know, we can reduce the these millions, hundreds of millions of people and thousands of miles to their regimes flags and sort of political sort of situation that you can sum up in a sentence or two Hmm.

Carlton Reid 49:21

In the prologue. So I’m going to go into bicycles. This is a bicycle podcast, I’m going to absolutely I want to go into the next geopolitics. Travel right I want to go into all of that in this conversation but I would like to absolutely zoom into the end of the bicycle part of this. And then in the prologue you talk about arriving on a bicycle anywhere and I absolutely agree with this because I’ve certainly experienced it. You are treated as innocent so that’s what you say in there. You know, because if that bicycle is too many people is a is a plaything. It’s something that their children use and then somebody coming up you know arrived on a bicycle is is unclear. threatening says that you, you’ve definitely made that conscious decision you could have, you could have walked in Israel you could have driven around Israel with with Arab drivers, you can have all sorts of different things. But it was a very conscious decision to use a bicycle, because that is a signifier of unthreatening person, slightly, maybe odd person.

Julian Sayrayer 50:25

Yeah, it’s got that eccentricity factor for whatever reason. I mean, to me, you know, 11 910 11 years now, since I cycled around the world, I broke the world record for the circumnavigation. And actually, this whole point of the bicycle is innocence. I think there’s a moment on the Canadian US border on that trip, where the US border guards who said can sometimes be a little bit gnarly. We’re sort of you know, where were you going to Tijuana at that point? It’s like going to Mexico. Yeah, sure thing through you go. And I just remember on that instant that But it really sort of diffused any tension. And so the bicycle in lots of ways has always just been the way that I travel. It’s, it’s the go to way and, and then that the book in lots of ways started out Edinburgh Book Festival actually in talking with an Israeli author. And I mentioned, you know, my travel by bicycle and this idea that you see politics at the side of the road best of all on a bike and she’d kind of suggested Wow, I mean a bicycle, you’d really see the reality of Palestine and Israel

Julian Sayrayer 51:32

in very close quarters.

Julian Sayrayer 51:35

So I think that kind of planted the seed in some ways and so a mixture of that sort of external suggestion actually from an Israeli that I’d see the reality of Palestine very clearly by bicycle, my own you know, I grew up riding a bicycle really I was, you know, I was born in born in the well born in London grew up in the Midlands, in a pretty sort of post industrial malaria, and having a bicycle was absolutely my way of getting out of this quite unremarkable place. You know, from a small town to get in, even into the lanes of Leicester share, it was a sense of freedom. And I do think a bicycle kind of resonates to, you know, to all those who loves what it is to be on a bicycle and feel the wind on your cheeks and in your hair and pedalling and this sort of, you know, the motion and the grace in motion of just riding is such a kind of a pure form of travel, I think, to those that have known it. And then in some ways that kind of, you know, that physicality, even that very sort of sense of freedom isn’t in itself in in kind of stark contrast to a lot of the politics of Palestine, Palestine in particular, where you know, you’ve got cycling clubs and the guys can’t necessarily go bike rides because of military checkpoints, because you’ve got maybe Three checkpoints between Hebron and Jerusalem and so you know even little things like a road you know your average cycling club in the UK where you’re thinking about you know your wattage or your average speeds or your your total time or your personal bests. You know if you’ve got a grumpy conscript whose only Israeli teenager possibly having a bad day and deciding to make life miserable for you as you go for a bike ride, that whole sense of joy and the freedom of being on the bike that’s compromised. So yeah, the the bicycle in some ways is kind of is woven into that way of being in the land or, or the way that so many Palestinian cyclists I met talk about it equally, they still have this sense that riding a bicycle is amazing. And said there’s also that innocence as you say, but also this kind of universality of everyone kind of knows what it is to to ride a bike, you know that first memory you have when you first learn to ride a bike or that first time maybe you go for a bike ride that bit further than you have done previously and the way it resonates.

Carlton Reid 54:10

And in the book, you talk about the bicycle being a leveller for those. So the Palestinian cyclists, if they got tagged up in, in cycling gear, the Israelis would treat them almost as though they were Israeli because they look Israeli because they’ve got cycling gear on.

Julian Sayrayer 54:33

Yeah, exactly. Yeah, it’s a funny one. This kind of assumption, if you’ve got your road bike and you drop handlebars, and you’re like, for maybe wraparound shades. Yeah, there’s just an assumption that road cycling is an Israeli thing, you know, with a good bike being an Israeli thing. So yeah, it’s fantastic. And again, really comes back to this idea of freedom that this assumption when you’re going up to a checkpoint that you’re probably Israeli if you’re on a decent budget. Jason gay means some Palestinians who don’t have the right to travel in, in what is essentially their own land, all of it from the river to the sea in some ways. Because all of that lunch should be free for people to move in. And they can kind of transcend those restrictions by being on a bicycle because of the strength of the assumption. There’s probably an alien, they just get word waved on through and say, to be speaking to policy, new cyclists from Hebron, which is, of course, right in the middle of the territory, and who have never seen the sea. And they they’d written to the sea Jaffa, in, you know, just south of Tel Aviv or up to Haifa even and then that kind of very emotional sense of journey of actually we get to go and see the sea. I mean, I’m sure there are some there are permits and you know, travel passes allow people to travel from the West Bank, into what is Israel territory in therefore go to the sea but the fact that there’s something that a little bit clandestine about the bicycle and that you can just sort of steal your way through I almost feel bad talking about in some ways because it was fantastic practice that obviously happens a little bit secretively and I need to do so

Carlton Reid 56:19

without can imagine it’s partly this like the MAMIL type factor you know it bicycling in this country and in Israel is partly you know a now an elitist thing to do so if you’re walking around and coming into checkpoints and you’re wearing what is considered to be elitist gear, then you’re gonna be waved through a bit more that there is lack of cycling being you know, very different for different class of people in in some respects, even though at exactly the same time. Cycling is for poor people. It really is. It confuses people because it just confound expectations.

Julian Sayrayer 57:03

Yeah, absolutely. And I mean, you know, maybe a Palestinian lad who works in a bike shop or in a in a hospital has to save more of his wages to buy this, you know, his team outfit that he wants to wear. Then you’re, you know, a stockbroker in Tel Aviv might, but he still loves I just as when I grew up, I really loved saving up some money and was really happy to get my United States Postal Service job jersey. And, you know, it still happens. And I mean, I think you’re right as well it sort of points to this elitism which is obviously the assumption that gets people waiting for a checkpoint but you know, as we know the bicycle and again this word of being a leveller, I mean, all of these differences that get thrown up by borders by walls by by document Are you know, that’s immaterial and illusory. And I think there have been instant you know, it’s very sad I spoke to one lad who, from Ramallah, you know, ride rides mountain bikes primarily because he doesn’t like the checkpoints. So you kind of have that interesting dynamic, the spatial nature of the conflict, mediates people’s decisions about how they might ride there might be more likely to ride trails, than on the road because of the absence of checkpoints. But even though you know, he would say that he’d met settlers out on the mountain bike trails and stuff, who you know, often just receiving it’s very simple case of racism, the the issue of Route, he’s an Arab, you know, and of course, he’s narrow. And that’s, that means nothing other than, you know, it’s an ethnic background, the language, it’s a culture just as just as Jewish and says, just as it is to be British. And out on the trails, who’s encountered racism, I think, you know, he made no secret of the fact that he’d also had good moments where that kind of kinship and community of the bicycle can kind of transcend these affiliate immaterial ethnic differences that we have. And ultimately, that’s actually in lots of ways what I’d want the goal of the book to be and its message and the you know, the the role of the bicycle in the region, I think is it’s something that gives people a reminder of how much we have in common, essentially, and how illusory the differences are. But yeah, so he, he taken more to trail riding to avoid the checkpoints of the roads, then equally, you’ll have people that maybe go join rambling and walking clubs, because in in two hours of walking, you’re gonna encounter fewer settlements or checkpoints or blocks than you would in two hours of riding. So it’s really interesting. Again, this kind of geographic spatial thing that when you’re in a terrain, as most of us in the West are that you can just take for granted your freedom of movement. It gets completely compromised in a sense In a militarised space, which is what Palestine and certainly the occupied territories is,

Carlton Reid 1:00:05

as interested to hit to read that the some of the scientists, you’re talking to the roadies, and they had actually snuck across to watch the Giro. And in Israel, which must have been quite a difficult for them to do and and be politically charged back home as well.

Julian Sayrayer 1:00:27

Yeah, I think I mean, I can’t remember if I mentioned people sneaking across it. And one guy that I spoke to had said that he specifically is from Ramallah. And, you know, residents of East Jerusalem, despite not having the right to vote in in Jerusalem or Israeli elections are able to move into Jerusalem so they could have gone to see it easily. The God one guy I spoke to in Ramallah hadn’t been able to go and he said that he would have done you know, he would have been really excited to see this international bike race with fame. As riders that he knew and really respected, he would have gotten to watch it, but he didn’t have the right to travel there. So he wasn’t able to. And I think that was a contentious that, you know, his position on that was itself quite contentious because there were I think it was an Israeli Canadian Real Estate magnate who paid the money, which was quite a massive sum for the jello, to start in Jerusalem in 2018. So that in itself isn’t, you know, an instance of what’s being called sports washing now, because it was tied to Trump’s suggestion that you know, Jerusalem is the undivided capital of Israel, moving the US embassy and stuff like that. So even the existence of the stage that was politicised in that way and some of the guys for example, that ruler and other people in the peloton were quite good. Making a making a statement of you know, this is being this is politicised and You know, we often say that sport or cycling whatever it is to be can’t be politicised shouldn’t be politicised. But often what it’s doing is inherently politicising. It’s just normally done to sort of endorse a business’s usual, that is mostly unquestioned. So the guy that I spoke to saying that he didn’t really care about that he would have just quite liked to have watched the race. Even he would have sort of had some pushback from some of his Palestinian mates suggesting that that was, you know, endorsing and endorsing this idea of a unified Israeli Jerusalem. And this is again as with the choice of wherever, wherever you go, rambling, mountain biking or road cycling, because of the territory being so, so controlled. And again, this whole 50 miles wide thing perhaps every decision there becomes so heavily politicised because ultimate The contention that the Palestinians are facing at route is a denial of their right to exist the denial of the fact that they were their denial of the fact that you know that their grandparents literally their grandparents had their houses taken away from you know, when Jewish paramilitaries were settling the occupied territories after 1948 I mean, these are these are very, very recent memories. And so it’s really hard for, for people to just find, you know, a deep politicised space in some ways where where things aren’t contentious? I mean, you see you have Palestinian, who cycling Gaza who have been, you know, shot up by by Israeli soldiers and snipers of St. Louis. The extent to which we as a cyclist in the West are able to take for granted the space and the conditions and the movement that underpins cycling because it is this amazing invention. allows you to travel so much further and faster than you normally could on your own as a human. And that kind of pure experience of this, this vehicle and this invention is still felt by Palestinian cyclists. But again, as I say, it’s so compromised by the political and territorial constraints that people have to live under.

Carlton Reid 1:04:21

So, the billionaire, the Canadian Israeli billionaire, you mentioned that is called Sylvan Adams. And right, he interviewed Sylvan at when at the Giro because he was the guy who brought the genome in and he part funded the Israeli was the Israeli cycling Academy that protein. When when so that was a piece of in The Guardian that I interviewed him. Now he he’s interesting in that he’s not just interested in in, in Pro Cycling. Yes, he’s of course he did aliyah, which means like he emigrated to Israel from from Canada. He’s Obviously, intensely nationalistic. But he’s also intensely cycling focused. So a lot of his money in Israel is actually being spent on bicycle infrastructure. So you’ve now got the Sylvan Adams bicycle network. Yeah. Just northwest of Tel Aviv. The there’s a velodrome gone up, which is the Sylvan Adams velodrome so I would like to think that maybe through cycling there can be some some meeting of minds that cycling transcends all of the crap.

Julian Sayrayer 1:05:43

Absolutely. I mean, and that’s always my hope as well. And I think that it’s not a you know, it’s not a baseless hope. I think there’s reason to believe it can help in those respects. But it can’t happen on its own. I mean, again, you know, friend from Ramallah was invited recently to ride in, in Switzerland, I think it was. And Israel blocked his visa at the last moment, you know. So I definitely agree that there’s, you know, there’s a role for the bicycle to play in this, you know, this meeting of minds and bringing people together forming a community. But it has to happen alongside other things around freedom of movement for Palestinians around freedom to travel around visas, and around the removal of checkpoints. And I mean, this is to talk about it from a sort of very Israel Palestinian side, which I think is illusory. There are a lot of people in Israel who don’t like being military occupiers who don’t like paying for Israeli soldiers and conscripts to guard, religious, quite extreme religious settlers inside the occupied West Bank who don’t want and who don’t want the reality on the ground to exist as it currently does. And again, I think cycling is, you know, there’s a kind of crossover often between cycling types. And I don’t necessarily even think leftists at all. I think it’s unfair to put it in that way. But when you’re riding a bicycle in a sort of car dominated society, which is basically the world, you’re kind of seeing a different way of doing things. And you’re also even if you are this quite well to do white male Fe, when you’re on the road, suddenly you’re vulnerable again, you know, you’ve got it, doesn’t it, only take some idiot in a car who maybe earns less than you who maybe doesn’t have as many university degrees as you whatever, can still make you feel very vulnerable and put your very life in danger. And I think that sense of vulnerability, and space and the fact that our road networks are inherently politicised and how much space they give to cars, how much space they give to cyclists that actually that’s almost quite an interesting starting point on understanding the political dynamics. So say Israel and Palestine because it’s again, a it’s a situation again, of people being denied space and people being made vulnerable in that space. And one of the first guys that I speak to a guy who’s a cycle cycle cycling tourist, sorry, touring cyclists, that was a term I was looking for. And I stayed with him in Tel Aviv. And he’s someone that had obviously been very involved in Tel Aviv community to get cycling networks put in, and he talks about, we would have been doing that 15 years ago. And it was kind of the weird sort of like eccentric thing. And now everyone in Tel Aviv loves riding a bike. And he’s kind of sort of more he’s gravitated much more towards doing work around Palestine and Israel, because it’s almost it’s kind of in some ways, similar to what we might have seen in a city like London, where the people who 10 years ago we’re going out on a limb to say build these bike bike paths Give it a segregated cycle lanes have now won so much of that fight that it’s it’s actually and thankfully being normalised to some extent. So someone there who’s has activist experiences initially in urban design is now looking more at Palestine and Israel and is well aware that there are people on both sides of these walls who love riding bikes and and yeah, it’s it’s it’s very much a way of bringing people together and and also just seeing cultural change I think he would suggest that McHale the guy in Tel Aviv would have suggested that when they were first talking about bikes in Israel that was the idea of the Middle East and country Hall people like cars cycling isn’t part of the culture. And now you even have the mayor of Tel Aviv saying we want to make Tel Aviv a cycling city or you have these bike trails. across the country. And so route as well, that’s an example of cultural change happening. The fact that the thing that is left that all the little there’s being impossible, it will never work here can happen, which I do think there’s an inherent optimism in that when when you look at something like Palestine and Israel and the impasse there, and how hard it conflicts with justice done often actually there is the potential for people’s minds to change and something that sounds crazy at one point to become very fashionable and suddenly what everyone wants.

Carlton Reid 1:10:36

Well, when I was in Israel when I lived in Israel, I lived in Israel for a year in the mid 1980s. I stick out like a sore thumb on a bicycle, certainly in bicycle paths. I lived within a an Israeli guy who later got so doesn’t really didn’t like the the Israeli system of going in the army, the time and stuff in He actually moved away. He lives in Mexico now. But he was so unusual to see a cyclist that we immediately bonded. Because in Israel, there was just no bikes. And now there are lots of bikes, a lot of our electric bikes and which be illegal in this country in that they are. They have powered electric bikes. But you’re right, absolutely changed and if that can change and such is a car centric society, then there is sort of a smidgen of hope.

Julian Sayrayer 1:11:36

Yeah, definitely. I mean, there is always hope.

Julian Sayrayer 1:11:40

I mean, the Palestinians in particular are just such an amazing source of resilience. Ultimately, it’s very hard to take people’s dignity away from them and you see it, I mean, it’s kind of interesting an idea of where a sense of freedom comes from, and where that hope comes from. And when you’re certainly younger, say millennial Palestinians who have grown up grown up with the border wall, and such extreme segregation within the West Bank, they still have a very strong sense of what freedom is, you know, they still rap with these incredibly sort of forceful lyrics about their home. They still ride bikes and love it, they still are in love with the fact that they can actually like Create Project point and get to the C heifer. In LA, they play music or dance. And I think, again, it’s this kind of immutable sense of where freedom what what induces freedom or that sense of freedom, and I definitely think that riding a bicycle is one of those things so you can, nature in general, you know, you see a sunset, you descend a mountain, I mean, it’s the most beautiful terrain and country and land free which to cycle and I think there’s there’s so much kind of natural beauty in sort of Understanding settings, that, you know, you sort of like feed your soul from that essentially. And it gives people the ability to, you know yet to go on believing that, you know, Justice will get done that peace will come I mean, there is really very little I’ve never really encountered much animosity whatsoever towards Israelis even then certainly not Jews among Palestinians. I mean, the foremost grievance is their desire for mobility for travel for rights for the the sort of access to a full life that we in the West just absolutely take for granted. And yeah, I think we’ve we’ve those justices served, I think that there’s always going to be opportunity for, you know, communities to form and as someone who loves cycling as much as I do, and who’s already always done it and, you know, similarly I’ve done youth work in London. With kids from very well off backgrounds and kids who grew up on estates and they’ve always remarked on the same thing of how, you know, the bicycle was was performed as this leveller. It gives people something in common. And again, I think, you know, metaphor in some ways, the way that a bicycle can change your transport system. I think it can be the facilitator in changing other ways of thinking and ways of seeing a world and its politics and the people in it. But he is

Carlton Reid 1:14:36

back to you. So I think people see bicycles and it brings out the best in them. That’s a lovely quote. Yeah. everywhere, but it is that that’s a nice quote from from from your work.

Julian Sayrayer 1:14:52

Yeah. Well, I think it does. As we say, it’s like that sense of innocence. That’s very interesting on say something like the the larger checkpoints at a camp like Columbia just on the edge of the West Bank and the Palestinians going back through the checkpoint have to go through these very militarised turnstiles, and the cars drive through on the roads. And as always this interesting factor for me to consider that here I am riding a bicycle. So of course, I’ve got a vehicle, I’m not going to go through a checkpoint, turnstile pen, it wouldn’t fit. But equally, I’m obviously not in a box of metal and glass in a car. So it’s the sort of fantastic sort of ambiguity in the middle where you’re not quite a machine, but you’re definitely not only a human in your way of in your way of moving and I think, yeah, it’s that is the essence of doing things differently. It’s that I remember what it was to learn to balance when riding a bike. I remember the first time I decided to sort of like really go for it going down. Thinking Yeah, I think on balance and, and yeah, people who have, you know, taught their kids how to ride a bike and seen that freedom come along. And I think also on a bicycle, you can’t really do an awful lot of harm to anybody. And yet you’re still very personal, you know, you’re still obviously a human being in a way that cars really you know, they really shut us off from ourselves and from one another and I think the very fact of the car windscreen you know, we spend lives in front of computer screens, you know, we we take a break off and now looking at a telephone screen, we, we watch TV to relax in front of another screen and then people move to work behind the windscreen. It’s like the entire world becomes kind of mediated through right angled rectangles. And it’s, it’s almost by definition of, it limits our view. Whether you’re on a bicycle you’ve got you’ve got full frame Under 60 degree or maybe 340 degree vision, and, you know, you can feel the elements and you’re moving yourself. And yeah, we’re living in a very kind of automated mechanised digitalized age. And I think it’s a big part of the appeal and the lower of the bicycle at this moment in history, anything you see in it really sort of blossoming within cities. First of all, because people are kind of somewhat starved of a sense of, you know, what is it to be human, you know, what is the life that I want to want to live? You know, I live in London and often my favourite part of the day, the time when I think most and best is my half hour cycling to wherever it is, I’m going to get two and a half hours like going home afterwards. And I think that’s one of the really special things about cycle touring you just that become your life, you know, that becomes, you know, a very sort of fundamental mode. Have travel stopping and eating you’re hungry when you eat so you really savour your food you know you sleep out in the desert under the stars in a place like Palestine and yeah it’s kind of reminder of how we could be living on

Carlton Reid 1:18:15

the same page now now I’ve got the digital version, not the print version, so maybe it’s not the same page and the print version on the same page is that quote I mentioned. I think people see bicycles and brings out the best in them. There’s another quote that jumped out at me and this is goes straight into the political because you didn’t shy away from from talking

Carlton Reid 1:18:36

political

Carlton Reid 1:18:38

stuff with with both sides. But this this one was was was quite like it and perhaps even got resonance for Brexit. And that is so this is but we are talking about the the Israel Palestine conflict here is and that is the solution if there is one is always one that nobody likes. Both sides have to have And I mentioned that because we have a peace plan. I’m doing air quotes here. We have a Trump peace plan where one side loves it. The other side hates it. Well, that ain’t gonna work. So So have you talked to your contacts across there about the Trump plan the Kushner plan and what they think about on both sides? And what do you think of that particular plan?

Julian Sayrayer 1:19:30

Yeah, I mean, it’s false. It’s a joke. You know, it’s been rejected throughout the region, including, you know, countries like Saudi Arabia that are increasingly close to Israel. Because there still is a sense that, you know, this Palestinian issue is is such a it goes to the heart, really of the region in lots of ways and it has to be an equitable and just settlement. So I think you know, a diplomatic level interest been mostly ignored? You know, I think that was what $50 billion worth of funding that Trump and Krishna were hoping to put together. So it really is more like a peace bribe than a peace plan. It’s like if we can give the Palestinian Authority enough money to sort of make that go away. But you know, again, you could geography doesn’t lie. And if you look at the map that was put forward as a proposal, you know, that’s, that’s no territory, that’s no country and there’s no real hope that what’s left on the ground there could could form a sort of viable mobile community of people connected to one another. So that’s a sort of political level culturally, like, you know, my friends in Palestine, who, you know, I follow them on social media, you know, absolutely water off a duck’s back to them. They weren’t expecting anything, and they’re sort of social media output across the day. You know, I had my friends who were interested in fashion, maybe like Adding photos to their Instagram feed that they have, you know, textiles that they were working with or templates they were working on my friends who were into bicycles were posting little videos from their bike rides. You know, it’s like it didn’t happen. And my friends in Israel, you know, some of them are involved in the political process, particularly Gilly, who’s featured in the book. You know, his training is as a lawyer, so his job is not really to, you know, he’s not essentially so he’s certainly not a campaigner, or politicised guy, he sort of seeks to to shape what an institutional response would look like. And so he sort of did a sort of pretty dry analysis of, you know, what is this proposal? How does it stack up compared to those proposals that we saw in in the 90s with arafat, and ravine and I think there’s, there’s a recognition that Trump and Krishna having not spoken to the Palestinians for something like the last three years, weren’t ever really gonna come up with something that that offered much to the Palestinians. And so yeah, I think this will, this will just be like a little bit in history. You know, Trump is a very controversial figure in the White House. He’s very close to Netanyahu and, and the Israeli ideal. And yeah, as you say, like everyone has to hate it. I think that’s a pretty crude way of looking at how something gets settled. But I would suggest there’s probably some unfortunate truth in it. And I really don’t think that the, you know, the Israeli certainly not Benjamin Netanyahu, I don’t think they have any problems at all with this proposal as it as it’s put forward, and it’s a proposal you could never accept, really, and it’s good that the Palestinian leadership which is often very close to To the Israeli state, you know, you could argue that the Palestinian Authority just provided sort of security services for on behalf of Israel within the occupied territories. You know, there are heavy problems of corruption there within that body. So it’s good that they also said, you know, this is this is not just this is not equitable. This is not dignity. And I mean, I think the main thing is, and actually, I think you’d find increasingly secular Israelis left wing Israelis who were targeted with, you know, as you mentioned, Brexit, left wing Israelis targeted with the most sort of vile and intimidating forms of abuse far greater than anything. I think the remain live leave divide in the UK ever would have stoked. You know, this isn’t a way for Israel to go about living within their own country. And again, to put it in terms of Brexit with you know, in the UK, or in the US the last few years with Brexit. We’ve seen how intense and unpleasant it can be living with this really deep festering political cleave down heart of your nation. And to be honest, that’s what Israel does. And you can’t really live in denial of that fact.

Julian Sayrayer 1:24:16

And so this whole thing of like being pro Israel pro Palestine, I mean, ultimately, the pro justice case is actually is found on both sides, you know, as a book talks about people in, you know, in Israel that are very much a part of the movement for justice and for peace. And obviously, the Palestinians too, I think there’s often a lot more common cause than than squeezes out into the news.

Carlton Reid 1:24:41

In your in the chapter is entitled sperm smuggling. So we discussed that. And there’s a there’s a, there’s a war going on, and that war is to have as many babies as possible. So on the Palestinian side, you can describe where the story smuggling comes from but on the Israeli side, especially on the the, the radical, religious, right settler community, but certainly even in not the settler community, but the Haredi community, the the Orthodox community, there at least pumping out as many babies as they possibly can. So it’s a it’s a war to try and get as many people on the ground because people on the ground need houses. And if you’ve got houses that it equals space taken over, which is territory, which is then about basically political, absolute. So tell us about sperm smuggling and what are people putting into plastic bags and then hoping?

Julian Sayrayer 1:25:57

Yeah, well, I mean, it’s one of the many stories I guess in the book But just becomes a bit unbelievable somewhat But yeah, I mean the the Jewish extremist who assassinated your Yitzak Rabin, the Israeli prime minister in the 90s has unsubscribed was on surprisingly locked up for life in Ramon prison, and then successfully petitioned the state for visits from his wife.

Julian Sayrayer 1:26:27

And

Julian Sayrayer 1:26:30

pardon Carlton?

Carlton Reid 1:26:30

Conjugal visits. In other words, they probably do things that you wouldn’t normally expect prisoners have somebody in a prison to do with his wife.

Julian Sayrayer 1:26:40