Your podcast catcher not showing in links above (black circle with three dots)? Loads more on PodLink. Show is also on Spotify. and Google Podcasts.

The Spokesmen Cycling Podcast

EPISODE 259: Cyclist Detection Tech With Tome Software CEO Jake Sigal And History of Road Equity With Historian Peter Norton

Monday 26th October 2020

SPONSOR: Jenson USA

HOST: Carlton Reid

GUESTS: Jake Sigal of Tome Software and historian Peter Norton, author of “Fighting Traffic: the Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.”

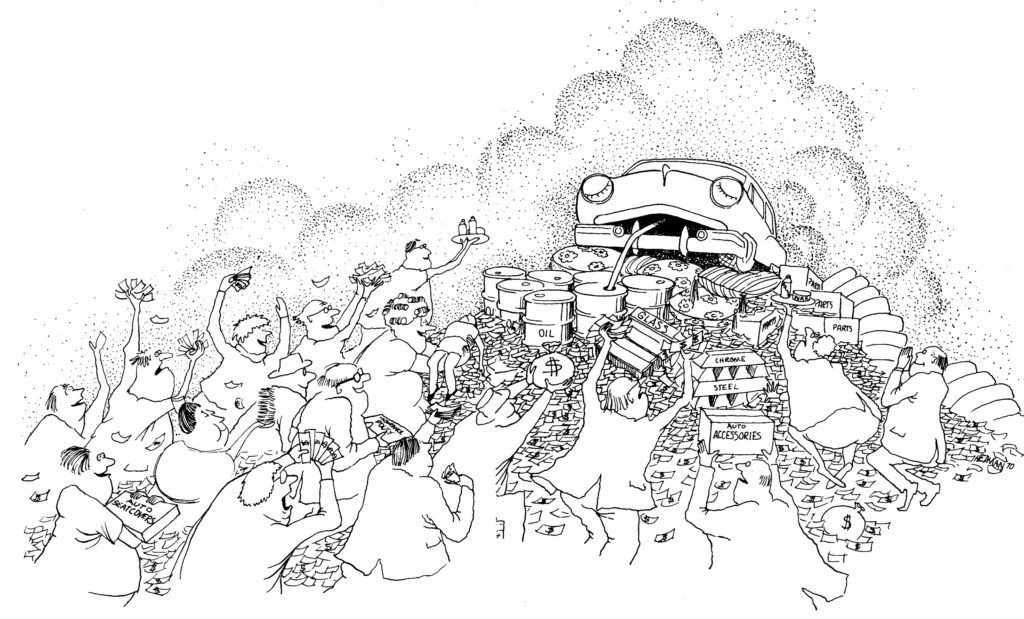

Cartoon by Richard Hedman, 1970.

TRANSCRIPT

Carlton Reid 0:13

Welcome to Episode 259 of the Spokesmen Cycling Podcast. This show was engineered on Monday 26th of October 2020.

David Bernstein 0:23

The Spokemen Cycling Roundtable Podcast is brought to you by Jenson USA, where you’ll always find a great selection of products at amazing prices with unparalleled customer service. For more information, just go to Jensonusa.com/thespokesmen. Hey everybody, it’s David from the Fredcast cycling podcast at www.theFredcast.com. I’m one of the hosts and producers of the Spokesmen Cycling Roundtable Podcast for shownotes links and all sorts of other information, please visit our website at the-spokesmen.com. And now, here are the spokesmen.

Carlton Reid 1:08

Hi there I’m Carlton Reid and on today’s show I’m discussing the detection of cyclists by the driverless cars of the future and the partially autonomous cars of today. My two guests are coming at this from two very different angles. First I talked with Jake Sigal, CEO of Detroit’s Tome Software and in the second half of the show I chat with historian Peter Norton.

Carlton Reid 1:35

Jake is a serial entrepreneur and, as he explains on the show, he sold an earlier tech company to automotive giant Ford enabling him to create Tome Software. Tome works with the auto and bicycle industries to create cyclist detection technologies for an increasingly digitally connected world. When every lampost, every road junction, every bit of street furniture, broadcasts its presence — and many already do — won’t cyclists be safer if they ping robot drivers and human ones too letting them know that they’re around the next corner? Jake and I discuss the upsides but also the potential equity and technology downsides to such an automobile-centred near-future, and for all my earlier worries about bicycle beaconisation — that cyclists need to be detected not connected — Jake reveals that Tome is also working on technologies that won’t need Bluetooth bursts or other kinds of proximity pulses. Jake is a passionate cyclist, off-road and for commuting, and he tells me that he wants what we all want: safer roads. In the second half of the show I discuss similar equity and technology issues with historian Peter Norton. Peter’s been on the show a couple of times before and many of you will already know that he’s the go-to guy for the social history of how automobile interests—what he calls motordom—successfuly turned roads meant for people into roads exclusively for motorists. His classic book — “Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City” — is a key tome, you could say, about the creation of jaywalking as a concept and soon thereafter a crime in many states, a creation that deliberately and cynically favoured one road user over another. In this episode of the Spokesmen cycling podcast Peter uses history to evaluate whether using technology to detect cyclists and pedestrians is the fairest and most effective way to keep them safe. As I said, it’s a long show, so strap in and let’s get straight across to Tome Software CEO Jake Sigal

Carlton Reid 4:03

Tome software, I mean, I know you because of the the kind of the work you’ve been doing on bicycles, and bicycle detection and cyclist detection, I should say rather, let’s use the agency here rather than the the form of transport. But what does Tome Software actually do away from cycling?

Jake Sigal 4:26

Well, we are a software services company based in Detroit, Michigan. And historically, we’ve worked with our clients on mobility projects helping with delivering packages or software that would help vehicles communicate with connected objects or people outside of the vehicle. So that’s been our basic model. And one year we were working we also had a client in the bicycle industry. We built some some connected cycling software products for for bike companies, and where they kind of married up as one could imagine. We’re at a bike conference and one of the folks from Trek Bicycles that based in Madison, Wisconsin, approached me and heard I was in Detroit and knew about our background with autos and asked about, you know, if we had the ability to work on getting with car companies to make safety products between bicycles and cars. And that’s kind of how it started. So outside of bikes, where we still do a lot of software for the automotive industry, we have some non automotive clients as well. And we are always interested in helping our clients understand how to create either cost savings or quality improvement. Sometimes it’s from new revenue for digital transformation, or formerly Internet of Things, IoT products. But a lot of our focus now is within connected vehicles and writing software applications for automotive and bringing it into a consumer electronics, which includes bicycles and environment.

Carlton Reid 5:51

So Jake, how long have you been going with Tome? What were you doing before Tome? So where did Tome come from?

Jake Sigal 5:58

Great question. So previously, my business partner and I, as well as our Director of Engineering, were a part of a company that was acquired by Ford in 2013. And that company helped connect apps and cars, this is now part of the Ford SYNC programme. After we did that, after after the sale, we around at Ford for a while, and then we’re thinking about what we wanted to do next, it just seemed very logical to take our experience and passion around connected car and bring it into things connected outside of the car. So the the old company was about connecting apps in your phone to the car, the new company at home is about a vehicle and connected to everything else around the world and anything else in the area. And that’s really how it started. So Tome is the company name, it’s an old English word for a book of knowledge. And we have this all-knowing owl buddy, which is our mascot, and it’s really fun. I’d say we’ve been at it since 2014. So great team. It’s it’s a it’s really awesome, we we have a strong focus on having people pursue to be the best version of themselves both both in work and in life. And it’s, it’s a great, great team atmosphere. I mean, even during the pandemic, as hard as it’s been for everybody, we did not lose any of our projects and maintain happy customers and just still able to keep a great culture. So we tell them, it’s a business that we started with a mission of making the world a better place around the automotive ecosystem. But I it’s not VC backed, like our previous company was was VC backed this one we own and we’ve got a few investors, but it’s, it’s, it’s really a company we built for the long haul. And we’re really excited to work with some of the best companies in the world. I mean, having Ford and Canon, the camera company’s one of our clients. We’ve done some project with NASA, I mean, there’s like so many cool projects with cool companies and just great engineering teams on the client side that we get the opportunity to work with. And that’s that’s basically Tome.

Carlton Reid 7:59

And how many people are in that great team of yours in in Detroit or spread around Detroit now, I guess on Zoom and stuff, but how many people have you got in the team?

Jake Sigal 8:07

So there’s 15 of

Jake Sigal 8:08

us full time. And then we’ve got a set of contractors as well that that work on various projects. So it’s a mix of that full time a contract, so a small company, and typically, we’re working side by side with engineering groups within our client side. So it’s a great business and, and you know, we’re able to be really nimble and fast with our size. So I don’t have to deal deal with a lot of overhead and clients. I think, like the fact that I’m involved on many of the projects or my business partners involved in the ones are not so we are able to really get hands on and solve problems for our customers in the industry.

Carlton Reid 8:43

And how did you get into that particular sphere into connected apps in thebeginning. Where’s your actual background from?

Jake Sigal 8:51

So I have a engineering degree, a systems engineering degree, and I worked in the consumer electronics industry and professional audio equipment and then consumer electronic audio, which led to a job at in Detroit, where I was product manager for cellular radio at the time, there was XM and Sirius in the US, two separate and then they merged. So a lot of background in audio. And we started the first company Livio, we were making desktop radios for Pandora and other automotive app companies and then and then started writing software. So eventually when the smartphone came out, like in 2008, when the iPhone one came out, it wasn’t a device, there was like the iPod functionality of the phone. But it wasn’t really it was not at that time a streaming media device. It wasn’t until about 2009 when, 2010 really, when people started really streaming audio from the phone, internet radio sort of started to take off. So one thing led to another and then we realised that the consumers didn’t need the hardware and that’s when we started getting into software. So it was very natural progression and all that transpired at the Consumer Electronics Show and was 2010 and we’re situated between the iPhone accessory group people section and then the automotive section. I mean, we’re literally physically between the two sections. And it was kind of like a lightbulb moment. And we’ve we’re still very focused on software that touches hardware. And that’s one of the things that makes us unique is we’re not just making apps. It’s apps that get get involved with hardware and Bluetooth and things like that. But yeah, just kind of solving the same problems, just different technology available to us to use our disposal.

Carlton Reid 10:31

And did you personally move to Detroit because Detroit obviously is, you know, the global automotive capital, or are you from Detroit?

Jake Sigal 10:43

I’m from Ohio, just just a state south of Michigan. And I was living with my now my wife or girlfriend back at the time, we were living in Rhode Island. So yeah, we moved back to the Midwest. And it’s not far away from where I grew up. And same type culture for any listeners that are familiar with the Midwest and United States. So a very natural fit. And I we when we moved to Detroit was right when the great recession started. So it like we were here at pretty much the downswing and now it’s become quite a vibrant community really fell in love with the area, just the amount of cycling and the culture of the parks. Other than December, January and February. It’s an amazing place to be in fact, I always joke with my friends that I don’t I don’t go and I don’t travel even for business between Memorial Day, Labour Day. So unlike the late spring, summer and early fall, this is where the only place I want to be. But when it comes wintertime we we jettison, so it’s when it’s five degrees outside, it’s not ideal, but for nine months out of the year, it’s fantastic.

Carlton Reid 11:45

So describe to me Intelligent Transport. So that kind of connected of things. So lampposts, traffic signs, traffic signals, they’re all now or many of them, no beaming out stuff. And cars, passing bicycles can now potentially be recognised as well. So it described that, that ecosystem of things that we don’t really think about these things, beaming information, but there’s things out there street furniture, beaming stuff, right?

Jake Sigal 12:18

Yeah. So I think that for the listeners, what’s important is to have technology that provides an increase in safety, but it’s still transparent to the user, it’s not something that you have to turn on or press a button. And the original technology to cross the crosswalk would be you have to press the button and then wait or be on a time system and hope that it would, the light will change. And with vehicles there, there used to be technology still in some lights where they have these sensors that would be embedded in the road to detect a vehicle. But those sensors were not able to detect a pedestrian or bicyclist or some other scooterists in the roadways. So a lot of that technology is already been installed. And you wouldn’t know that because you don’t have to download an app or do anything for it to use. So what we’re looking at and is ways for increasing safety while still maintaining the ability to not require users to have to press a button. And if for example, there’s been some technology out that was released I think it’s called Project Greenlight, not our company, but it would allow a traffic light to wirelessly recognise that a biker scooter is approaching an intersection to trigger to the traffic light to turn green when you know that you’re there. And as a cyclist, I can tell you that I can tell you the routes I ride and where that where you have to ride to the sidewalk, get off your bike and press the button otherwise, you’ll never get a green light or you’re you’re given that choice of trying to play Frogger across the road. So a lot of these technologies that we’re interested in involves something called signal phase and timing or SPAT and then separately there’s wireless technology which is coming with cellular V2X also known as C-V2X or CV2X which can communicate from sign to sign or car to sign or sign to car. So once that is set up and enables messages to be transmitted between the devices, so are companies really thinking about the applications so so what is like the so what factor like why would somebody care that these signs are connected? Well, if it’s a streetlight, it would want to know when it turned on at night so so it can be you know, not under the daylight or, or be able to fluctuate when there’s there’s people that would need to have access to that light and not create, you know, any sort of light pollution or other issues. But for safety features, we’re thinking about how to leverage these types of connected infrastructure for sending just very simple messages so that safety systems on vehicles can do a little bit better job or have a little better confidence for things that they can’t see in front of them.

Carlton Reid 14:55

And how much if this kind of Intelligent Transport Systems, that’s what it’s ITS? Yep. How much of this is absolutely 100% necessary for these famous — and we haven’t got them yet and they’re always touted — driverless cars? And how much is the the cars that are going to be like coming along in the next three, four years? Or perhaps even now? So how much is of this infrastructure necessary for the driverless cars? And how much is it just as necessary for the piloted cars today?

Jake Sigal 15:30

It’s it’s really a balanced approach with the technologies and the value of the technologies. So there are driverless vehicle systems that do not rely on any wireless messages from signs. So one could argue that none of it is necessary. But I think that there, I think that everybody would agree with more information is better. Now what you do with that information? Do you trust that information? Is the information accurate? And is it timely? Those are the key questions that we’re getting into. But just to be clear that driverless cars are level five autonomous vehicles like no steering wheel. Right now, there’s a lot of cars that have safety systems called ADAS systems that are level two or level three autonomous vehicles that do have a driver and have a steering wheel. So things like emergency braking, or the adaptive cruise control or lane departure warnings, those are really relevant, because it’s now looking forward in the future about what you have to have on vehicles, it is going to be a function of the driving speeds and the location. So for trucking that are on an interstate going from state to state, it’s going to be a different set of requirements than manoeuvring a dense urban environment. And I think that those teams are still evaluating how to continue improving safety, I would say that I always have people asking us a lot is your how would you feel if there was an autonomous vehicle behind you? And what I tell people is that at this point in time, and they actually have about a year and a half ago, I feel safer having a robot behind the wheel, when I’m running, when I’m personally riding a bike, then the average driver because I don’t know if the average driver is distracted. And if you’re riding a bike around rush hour, there’s also an issue where you have a lot of obstructed vision. So a autonomous vehicle or a tonne of safety system in a vehicle that with a human driver, I think will be another set of eyes, another set of resources to see me while I’m out riding. And that wasn’t the case five years ago, but now I would say that the safety systems are great. And there’s always going to be edge cases and use cases. But I think we’re at a point now where it’s it’s clearly increasing safety. And yeah, you’re going to see the reports of, of tragic incidents that happen. But I’ve met with a lot of engineers working on these systems, and they’re doing it because they’re on a mission to make make the world a safer place and reducing injury and death. And that’s, I think we’re at a point now in the technology where it’s better now than the average human driver. Again, just my opinion, but I’ve seen this from the inside and outside. I know what sort of technologies are there and you know, the just even the the reaction time to recognise it’s a cyclist versus just some object up ahead. I mean, those are things that, that with the right technology can really help a human out that’s behind the wheel.

Carlton Reid 18:27

At the humans who are not behind the wheel, there’s some jargon here. So this is not it’s not your jargon. This is just the jargon and the industry. But it’s kind of you understand this. So VRUs so vulnerable road user is the jargon for a pedestrian, somebody on a scooter, somebody on a bicycle. Now, in the future in your technology, or just this the general connectivity, technology that’s coming are VRUs, are vulnerable road users, are they going to have to use a smartphone is that smartphone going to have to be turned on? What’s the technology that a VRU is going to have to have?

Jake Sigal 19:10

No. So we are very, we’ve been very clear, our 20 companies on our advisory board, have been very clear that that we need to support vulnerable road users, pedestrian, bicycle, scooter riders that do not have do not want to have or their battery is dead and their electronics that we have, we have two very distinct groups, which we call an unequipped VRU or someone that doesn’t have any electronics, or they’re choosing not to broadcast electronics, even for privacy reasons. And then if you have the electronics, whether it’s built into a shared bike that you get on and ride so as a user, you just ride the bike, you don’t have to do anything it’s built in or all the way to an app on your phone that can provide some level of identification – or device classification in other words- letting a car know that you are a pedestrian versus a like a… For example, let’s say you have a bike on a bike rack on a bus. Well, if you accidentally left your your ebike on and the motors on, it’s not spinning but it’s on the bus, we wouldn’t want a vehicle to think it was about to run over a cyclist when the bikes on the front of the bus and you’re riding the bus going down the street. So we really think that there are two paths, there’s the unequip VRUs as someone that doesn’t have the electronics and whether for a number of reasons, including equity reasons, they may not be able to afford the technology that we need to make sure they’re protected both from vehicle systems as well as protected from the ITS, the signs and infrastructure. Now, if there is an opportunity to have a low cost, wireless transmitter that can transmit anonymous information, things like ‘I am a bicycle, I’m travelling north, I’m going 15 miles per hour or 20 kilometres per hour’. That is useful information that helps because GPS does not work very well for tracking a bicycle or scooter. So I imagine many of the listeners, you had an experience in a city where you had the little blue dot on your map and it kind of bounces around a little bit or you’re driving using the Waze app or Google on your car and you’re like on the freeway, and then it thinks you’re on a side street and it jumps back to a freeway. That’s in GPS, this happens where it gets a little bit out of sync, because it’s pulling information off the satellites. So getting direct information off a bicycle or scooter like electronic compass, a speed from a wheel spinning, just some basic information even saying I am a scooter and I am moving that that is some really useful information on a low cost sensor that the having that information. While it’s not enough for a car to slam on the brakes, it is enough for a car safety system to include that information provided it’s trusted, so that the car safety system can do a slightly better job or be more confident in the decision that it’s going to make to help help avoid an incident or alert a driver. So that’s kind of how we look at it is that, that there are some opportunities there. The the opposite of this would be let’s put a $200 doodad on every bike and scooter. And that’s just not gonna happen. So it’s just not gonna happen. I mean, in vehicles, there are basic safety protections and those increase over time, so seat belts became mandatory. And there were lap belts. And then you have the cross strap seat belt then airbags were optional feature. And now they’re mandatory than others. Now you can get vehicles that have 20 airbags and increased safety systems. So like Lane Departure warnings, backup cameras, I mean, all these things are optional, they come in standard features. So I do think that there’s a really good precedent set that if you’re a cyclist and you want to increase your safety, you can buy a helmet, you can buy a bike light, you can buy a reflector reflective armband, or straps. So you look more like a human being and not just flashing light out there. So there are a lot of options on this and start to be a little long winded with this. But I want to make it very clear that that we want to provide options for people, but not leave anybody behind. So there will be more benefit if you’re having electronics. But at the same time it’s we can’t just say okay, now everyone on a bike has to have this electronic device. That’s just not not feasible. And we look at this as finding solutions for all riders regardless of their ability level, their age, their economic status, whether it’s their own bike or share bike, or a scooter or E powered bike or a regular powered bike. For us the Vulnerable Road User includes everybody, we got to make sure that everybody is included in our work.

Carlton Reid 23:29

Everybody’s included, Jake, but is it not the very fact that this could be two tiers of road user, vulnerable road user, in that you’re going to be equipped or not equipped? And this is purely hypothetical. I’m sure you’ve come across this before I’m sure all your workshops with with bicycle companies this has been broached. But in for instance, in a future litigation, where a cyclist and this happens with helmets, this happens with high vis this happens with lights already in in a court case where a motorist hits a cyclist. A lawyer at some point will say, ah, but that cyclists wasn’t equipped with this latest Bluetooth beacon. That’s why the crash happened. And what then happens is that the whole blame isn’t apportined to the cyclist, but a certain part of blame is apportioned. So then it becomes absolutely two tier road system. So how can that be? How can that be kind of like stopped before it’s even started?

Jake Sigal 24:38

Yeah, I understand the point. I don’t fully agree with the point about the two tiered system. And let me let me talk a little about that. So in our opinion, these cyclist does not want to get hit by a car any more than a driver wants to hit a cyclist. So it’s not just about responsibility. It’s it comes down to accountability. So, for example, if a cyclist is riding the wrong way on the road, in a vehicle lane and is breaking the law, he or she’s responsible for taking that action, just like if a driver of a vehicle is driving in the bicycle lane, which we’ve seen that happen, that that driver is then responsible, and especially for commercial vehicles that we double parked and other types of situations. So I definitely understand and see that point that comes up quite a bit. But from our work and experience, we’re really focusing on the use cases where everybody’s doing the right thing. So if everybody’s doing the right thing, there shouldn’t be incidents happening anyways, except for some really limited circumstances where the driver has obstructed view, like coming up in over a hill, or you’re driving West at sunset and you’re, as a driver looking straight into the sun and you’ve got the visor down, it’s really hard to see those types of limited use cases or areas where we think the technology can really help. So if a cyclist doesn’t have this technology, and there’s a litigation around, should the cyclist have had this? I think it’s going to come down to what every governing body whether it’s a state by state, or municipal level, in the US, we’ve got federal, state and local regulations and requirements on this is just going to be me based on the vru style. So it’s very possible that for example, if you have a moped like an actual motorised vehicle, like a motorcycle, you are regulated and having certain things like having lights having a licence plate, I don’t think a pedestrian should or whatever have any of this, I personally don’t think that a bicyclist, whether it’s powered or not powered, should have any of this or any scooter should. But ultimately, it’s up to each group to decide what should be there and what the use cases are. So what I wanted to just kind of put a little colour on this is that this two tier road system, we don’t see it that way, it certainly is possible. But what we see is dense urban environments having a three tier system where one is vehicle only. So in New York City, you’ve got the West Side Highway, or Second Avenue, and it’s I think it’s Seven Av that’s car only. And then you’ve got bike and VRU, Bike Share plus Car Share areas. And then separately, you’ve got bicycle and VRU-only areas and in Europe, that’s pretty common, as well as having these bikeways that are that are developed. And then there’s rules and regulations for the bikeways. So being a proper user of a trail or road. That’s not a new thing. I think that’s going to continue. But trying to say that because technology to make you safer exists means you have to wear it. I mean, that’s not something that we engage on. I mean, our mission is to increase safety and make sure that we can increase safety for both equipped and unequipped. The argument of should helmets be mandatory. I mean, that’s that’s not that’s not our fight to fight. I mean, I’ve got my personal opinion as a rider. But I mean, ultimately, that’s that’s, that’s up to local state and federal jurisdiction on that. So I see your point there, but we kind of see this a little bit differently. And I hope that hope you understand that from our standpoint, we’re just trying to increase safety and make sure no one’s left behind. And there will be some questions asked on this. But ultimately, if we’re increasing and saving lives, I think that it’s it’s worth having these harder conversations about these types of issues if we’re ultimately reducing the serious injury and death count with the technology we’re working on.

Carlton Reid 28:41

So what do you say the technology then is it like an equivalent to you know, all day running lights or wearing a helmet or the hi-vis, in fact these are all optional things. You don’t have to have these things. Many cyclists don’t have these things, but it just increases how visible you are to motorists. So if you’ve got the you know the standard, you know, Bontrager type, you know, always on, yeah, daytime running lights, you’re going to be that much more visible to motorists. You don’t have to have them. But you know, it’s your own. If you want to save your skin, then then it makes sense to have them.

Jake Sigal 29:21

Yeah, so personally, I always ride with high visibility, reflective and daytime running lights and a helmet. I wanted one day during the pandemic, I went to pick up some food and I didn’t put a helmet on I’m just going a few blocks down the street and I felt naked like I was like, I literally forgot something my helmet on and that’s just that’s me, that’s me is personal. That’s That’s me as a cyclist, but it’s not my decision to make for how other people look at this. And some people, rightfully so I would say that as a cyclist. They should need to do this in order not to get run over by a car they just shouldn’t be getting run over. And how I respond to that is that I understand and your rights as a cyclists in your country in your city in your state. I mean, that’s, that’s, again, what we talked about earlier. But if I can make this safer Is that a problem. And I think that where we draw the line is that if we make technology that’s mandated and somebody is left out of it because of cost reasons or some other factor, that that’s not a good thing. Because then in a way, we’re creating a false sense of security for some riders while we’re leaving other people behind. So I agree personally, when it comes to the choices that I make, and why I make them, but I also respect that other people may not agree with that position and might feel differently. So as long as we’re providing options for people I that’s why our team is on mission and doing this and I believe that bike companies are aligned with this is providing options and making sure we’re covering both equipped and unequipped vulnerable road users out there.

Carlton Reid 30:50

Because you know Bontrager daytime running light $80, $90 You know, a lot of people are riding around on bikes that are worth $60. And they’re the ones not going to be you know, protected. They’re kind of like the kind of like, called, they’re invisible cyclists in that, you know, huge mass of people are out there on bikes, but they’re crummy bikes, they’re not very good bikes. But there’s lots of people out there, and they don’t tend to have any safety equipment. At the moment.

Jake Sigal 31:18

You know, I tell you that in Detroit, I see a lot of people that are riding and I’m you know, since they’re not wearing Lycra like like I’m sometimes I’m assuming the ride to work or home from work. And they do have a safety vests on and they have reflectivity, and they’ve made that decision. So I think that there are a lot of different ways to be more visible. And with the type of work that we’re getting into it just I think education for the cyclists is really important. And we’ve worked very closely with Ford Driving Skills for life, which is funded by the Ford Foundation for driver education about how to look for cyclists and how to properly approach slow down and pass a cyclist in Michigan, we have a three foot passing rule. And it’s almost like you could take one of those, the swimming pool noodles off the side of your bike. And that’s how far away that the driver supposed to pass and create some awareness, there’s been more signage about owning like taking a full lane as a cyclist when it gets a little sketchy on a bike. So a lot of these things are happening at a advocacy level and education level, which we fully support with our company, we are really involved on the tech. So understanding the behaviour of cyclists, how cyclists ride, and we’ve also started to take a look at the type of cyclists so road bike child on a children’s bike, looking at share bikes, what sort of acceleration and deceleration how fast they go, how fast are they stopping, and looking for these types of trends so that we can make the vehicle system a little smarter. But like I said earlier, that from our standpoint, we’re trying to find ways to make cycling safer, and we don’t want anybody left behind from like, what should cyclists be wearing? I mean, I’d encourage all cyclists to put a helmet on have some form of lighting or reflectivity, neon lights during the day it the stats show, it’s going to make you safer and everyone knows me, I’m like Mr. Neon going around during the day. But you know, some people think that looks so cool. But you know, it’s it’s a obviously a personal choice and if we can make technology to help help think cars See you when even when you’re beyond line of sight and that’s a good opportunity.

Carlton Reid 33:26

And what do you see the technology? How do you envisage eventually getting out to the market so things like you know, the Garmin radar product which they’ve got your that could be like beefed up with more tech like See Sense. I know See Sense is on your your website? Yeah, as you know, Northern Ireland company that makes some great technology. Yeah, you know, their lights, they’ve got some clever electronics in there. So are you thinking in the future, then how long in the future but there’ll be like, augmented products out there? So it’s not gonna be like a like a transponder that you fit to your bike? standalone, it’s going to be integrated in other electronic devices. Is that is that the way you think it’s gonna go?

Jake Sigal 34:09

Oh, absolutely. And like I said earlier, the technology needs to be transparent to the user. So it’s not some black box that you turn on when you’re riding it’s it’s built in. So we’ve talked to a number of companies about putting it into ebike drive systems so electronic bike it’s got a big battery already has wireless connectivity makes a tonne of sense. We’ve talked to car companies about being able to connect a sign so that if a sign sees any cyclist without any electronics that that message can be received and determining what the safety messages we have a white paper on our website for engineers on topic. We’ve talked to university researchers about this and we held a our first annual conference last year we had a postponed due to the pandemic of course this year but on same topic is like what are the dynamics what how are these things moving? How are the devices moving people on scooters scooters by ebikes different types of other VR use wheelchairs, that sort of thing. A lot of different options that go into this. So I think for us, it’s, it’s really about making the technology as seamless and transparent to the cyclist and the driver. And our companies are really looking towards that I don’t envision there being any black box that’s that’s put on your seatpost. That doesn’t mean it would be incorporated into something that is already on the bike or something you need. Now, of course, you’re going to retrofit so if it’s an a helmet, if it’s on the handlebar, if it’s in a bike light, these are all areas that we’re very interested in. And I can speak for my experience working with the bike companies is that this is not something that they look at as competitive technology, they look at this as creating global standards for how to communicate their presence and and let in such a way that that protects consumer privacy keeps the cost down, and can be really driven into mass volume for, for adoption across all cyclists. So that that’s kind of the area that we’re looking at is different products as this can fit into. But while maintaining that there is a trust level from the auto company that when they get a message from one of these devices, that it’s a proper message and see sense of I want to give them a plug has been absolutely fantastic to work with, as with our other core groups and our prototyping Working Group. But it’s just been really good talking to companies about ways to see where the technology can go, and then find ways to really keep the cost down to get into more more more saddles and more more riders in the world

Carlton Reid 36:37

Is going to be cheap, basically? So people that adopt it?

Jake Sigal 36:41

I would say that if we do this, right, it would be built in to products that you’re already buying. So it’s a very cheap, affordable incremental upgrade for them for some basic protection. So where it gets really expensive is if this turns into a vehicle to vehicle trusted message. So I mentioned earlier, if a bicycle is transmitting some basic information, that’s pretty affordable to generate deliver, if we had to generate the same messages that a vehicle generates, it becomes very expensive, very quick. So I would be very surprised if that’s the direction this goes because it would put sensor requirements on a on a bicycle or on a wheelchair or something that are well beyond what the cost of the bicycle or wheelchair would be for the average rider. So we’re really looking at ways that not only are technically feasible, but also feasible for the market. And that’s not our call to make at Tome that’s why we brought on board the best bike companies in the business. And I want to point out that in addition to having Specialized and Trek and Giant as part of our group, we also have the Excel group and other companies that are working on like Dorel Sports that work on bicycles that are found in department stores and other entry level bicycle programmes. So it’s not limited just to the high end bicycle market, which really helps us make sure that what we’re working on is feasible. And then on the auto side, same thing, making sure that the technology we’re working on would be feasible to bring into a car. So we come up with something that’s super cheap and does something but the auto guys wouldn’t trust it for a good reason, then that’s not going to work either. So that’s a balance between the two industries is something that we have a lot of experience with working at Livio, or previous company with ABS and cars. And, you know, we’re doing that same playbook going in to tell them with with this, and it’s not a Tome technology. By the way, this is technology that will be industry standard. It’s based on SAE automotive industry standards, and working on the same playbook that the auto companies have been doing for the last 20 years. So for us, we’re really facilitating and organising the effort, but it is a industry is a cross industry, open standards effort where it’s not proprietary tech, you’re not gonna see at home our logo on your bike any day, this is really about making the world a safer place and agreeing on global standards. So any startup any large company, any auto company could could access this.

Carlton Reid 38:58

So you mentioned the kind of the packages of information that gets sent out there. And I noticed from our email conversation we had to begin with, there was something called BSM, so that’s basic safety message, and then there’s PSM personal safety message. Are they the two different expensive and or cheap versus expensive? What are the what are they? What are those two things?

Jake Sigal 39:20

Well, messages. So they’re two separate messages. They’re very similar. And the basic safety message is what’s been adopted by automotive companies. The personal safety message has been submitted as part of the SAE [Society of Auto Engineers] standards, but it hasn’t been fully adopted and fully adopted, there’s a bit of an asterix there. And you might be what was that mean? Or what what that means is that we just need to do some more research and really determine what’s in the message. messages are free, by the way, like it doesn’t cost anything to send a message. It’s like typing an email that’s free, but generating the information that’s in that message and then having a wireless system to send that message that that’s where the cost comes in. So they are related. So what’s in the message If I say, here’s my location, but I’m using a GPS receiver, it can be challenging because if you’re in a city, that location may be wrong. So can you trust that location, or if you’re pulling it off a mobile phone, and your phone’s in your pocket, what sort of signal coverage you’re going to get in your pocket your backpack versus having your phone mounted on your handlebar? So the real interesting part for us at Tome is defining the message requirements. So like, what are the like, How fast are we sending this message? What’s the accuracy level, and then the performance requirements of the sensors that are generating the information. Now the sensors could be on sign, could be on a vehicle, or it could be on the bike, or scooter or other VRU itself. So for an unequipped VRU, someone that doesn’t have a phone or doesn’t want to use it, it’s one of the minimum requirements, you have to put on a sign or a vehicle to then send other signs and vehicles that there’s a bike out there, and that bike is heading north and the bike is going at the speed. So that’s really where the challenges so between the the basic safety message and the personal safety message, we’re all working together on like, what is what vehicles need. And we might find out that we need to create a different message and take a light version of the basic safety message or reduce version specifically for vulnerable road users. We’ve had tremendous support from SAE, we’ve had great support from the Crash Avoidance Metrics Partnership, which is a group that GM and Ford created 20 years or so years ago. And there’s got to be 15 automotive companies participating in that. And they’re also partnered with the US Department of Transportation Federal Highway. So we have some really great [adversaries] talking about just the work that needs to be done for a long road user and a playbook to pull from. So I think when it gets down to BSMs, and PSMs and the message formats, I wouldn’t get too hung up on that, at this point, what’s important is understanding and balancing feasibility cost, and what’s the minimum set of information that a car needs to know in order for it to do something different that it can trust, and it’s got the right accuracy level within the message?

Carlton Reid 42:02

And how much of this is North American lead? Because you can imagine, you know that that scenario you said before where you know there’s a light is the sunlight is is low? There’s a cyclist over the brow of a hill. And then there’s one cyclist, you kind of you can you get that information, the driver gets the alert, and you’re golden, because you’ve spotted the cyclist. If you’re in Copenhagen, if you’re in Amsterdam, you’ve got 20,000 BSMs or whatever. Yeah, coming at you like crazy. Yeah, so how much of this technology is like a North American mindset versus like a continental Europe where cycling is you know, like, you know, vacuuming your carpet and brushing your teeth. It’s so normal. Yeah, it’s, you know, you Dutch person would say you want me to do what? You know, with my with my, my phone or I need to have what equipment in my bicycle? What, are you crazy? So how much is North American compared to European.

Jake Sigal 43:07

So we are coordinating with COLIBI, which is the European cycling organisation. We’ve talked to a number of companies out of the Asia Pacific region in Japan and Korea, and there are different use cases. So congestion of cyclists, fortunately, makes cycling safer. Now the more people that ride bikes, if you take a percentage, the more the more number of incidents you’re going to get. But from a percentage standpoint, it’s safer numbers. So what we’re finding and talking with different groups, and even if you look at downtown, like looking at New York City versus a rural area, in the Midwest, with dirt roads, you have these different use cases. So from our perspective, we’re really interested in finding the areas where there’s a high likelihood of a serious injury or death and defining that vulnerability. So we don’t define the vulnerability there’s research out there that defines the vulnerability or in layman’s terms like a danger that you’re at any given time. So not only do you have to feel safe riding a bike, you have to be safe riding a bike, and the vulnerability indices that have we looked at as a six different sources. We’ve modelled this with the US Department of Transportation’s model for vulnerability, that’s those are the areas we got to watch out for. So in a massive area, we’re not saying let’s have 100 bikes in Copenhagen send out 100 messages and that situation we look to a science say let’s let the sign detect that there are a lot of bicycles in the area, and then adjust the signal appropriately when the bicycles are crossing a major road, which is a lot different than in a suburban or rural area by letting a bus know that hey, there’s a cyclist up ahead. And if it’s after sunset, then that may be a different indication to the driver than than if there is like five bikes around and it was in a bike lane. So the situation that the cyclist is in It’s not so much about the part of the world they’re in, it’s really around the density and congestion of the VR use. And also want to point out that we are not looking at alerts for drivers. If you got an alert, every time you saw a bicycle, even in Detroit, you would turn off that notification in five seconds, because they would ding you every every three seconds, it just be, it’d be super annoying. But what’s really useful is looking at those really tricky areas where there’s high vulnerability, and also having the right amount of information for a safety system. Same thing with autonomous vehicles. I mean, we, I think, many of us if you’re around the space, you’ve seen this, where if you’re driving in New York City as a human driver, and this comes up with autonomous vehicles is that pedestrians will stand right at the edge of the curb, and you have to slowly move out and go through on the green light, pedestrians will do what they’re supposed to do. And it’s kind of how it works in New York City. When I was in Asia, same thing. I mean, it’s, you’ve got just people and VRUs, and it’s everywhere. So like the use cases, there’s going to be areas where our technology does not make a lot of sense, because it’s an extremely dense area. But then there’s other areas where it also might be so rule that you need a data connection in order for it to transmit messages. And that doesn’t make sense either. So we’re still looking at finding the sweet spot of where this goes. But for anyone that’s riding in mass numbers, I’d say that this is not like you get an alert or for that you made the comment like the person in Europe says I’m supposed to do what well, the basic idea here is that you’re not supposed to do anything, you’re supposed to ride your bike and vehicle drivers and the vehicle safety systems, we’ll get some awareness where you’re at. That’s the we’re not asking anybody to do anything at this time. It’s really just finding ways for for infrastructure and existing bike products to help help keep people safe.

Carlton Reid 46:51

So before we talked about a hypothetical court case, where it was the lawyer was, was going at the cyclist for not having the right equipment, could we maybe flip that and say in the future, potentially, if this technology becomes ubiquitous for both bicyclists motorists, pedestrians, and motorists, it then becomes incumbent on the motorist that they have been given all this information. And the lawyer could then say, forget, there’s sunlight blinding you that will no longer you can’t use that excuse anymore. You were given that information, there was a cyclist over the brow of the hill, you chose to ignore that information. So it could potentially this technology actually flip that kind of court case where cyclists tend to be squished. And the driver, you know, just comes up with some lame excuse. And then you know, with with a jury of murdering peers, they get off with it. So in the future, could they no longer they won’t get off with it.

Jake Sigal 48:01

I couldn’t comment, I’m not an attorney. And obviously, it varies by area, I just go back to, from our perspective is people want to do the right thing. And if we provide information for a computer system, and there’s no notification of the driver, it certainly eliminates that type of a situation. But for a lot of pedestrian identification systems are out there now they’ll have an LED that pops up and and then kind of creates that awareness that there are pedestrians in the area. I know that that one auto company even does a simulation to show you pedestrians and bicyclists that are around you while you’re driving. So this already is existing and production. And these types of questions always come up. But I try not to engage too much in hypotheticals because in some in some respects, I look at this and say, well are what what are we supposed to do are supposed to just stop making the world safer? No, we have to come up with making the world safer. And we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it on some of the other issues. And maybe there’s some use cases that need to be taken out because of liability issues or confidence issues. More importantly, that, that we think something’s there, but we’re not sure. And that’s not new, that’s what the industry does today. And if we can find a way to save one life with our product, it makes it worth it. So that’s how we approach this and apologise to be a little bit evasive at the base of the question. But I mean, from our standpoint, it just really comes down to look we’re making, we’re making it safer. And we hope that by doing what we’re doing, even if there was a court case that came out of this, we would be saving lives and in my mind that makes it worth it.

Carlton Reid 49:41

Yeah, and I apologise to you as well, because it was a hypothetical. And it basically has to be case law. So at some point in the future, I’m sure case law will will grapple with these issues. These things will come up because it’s no longer there’ll be some excuses, you won’t be able to use anymore both both, probably both, all road users will no longer be able to say, you know, they couldn’t see you. Because it’s like, well, the electronics were there, of course, you could see then you chose to ignore that. So that’s case law. That’s hypothetical. So final question, Jake. And then I’ll let you get away, because I’ve taken up a lot of your time. Thank you. And that is when maybe this is another impossible question for you to answer. But when might we see this technology? When can we go into a shop? Do you think and and get, you know, a light a helmet, or whatever, with this equipment with this, with this technology in.

Jake Sigal 50:39

So our vision is, in the next three to five years, this technology will be saving, will be increasing the safety on VRUs on the roadways in the next three to five years, there are some things that need to happen for that to go. So and also with the pandemic, it’s it’s hard to say with some of the timelines, but with our relationships with the auto companies, our understanding of the technical readiness levels needed for the sensors in the broadcast system, this is three to five years out, which in auto terms is fast, by the way, but this is not next year. But we’re not talking about Jetsons flying cars, we’re not waiting for autonomous vehicles. This is much sooner than that. And again, I want to just stress that this is not going to be only for new bicycles, or only for new cars, I mean, this will be something that would be able to be rolled out not to all vehicles. So if you have a car today, it probably won’t be included on the vehicle you’re driving today. But at some point, these will able to be software updates. And we’re really excited about just the opportunity. So in auto terms, I’d say it’s we’re following the right steps in next three to five years, we’ll have really clear safety methods for in vehicle. And for infrastructure. It’s already started, I mean, infrastructure already is working on and including bicycle protection in some areas in the United States. There are pilot studies going and they’re doing connected corridors, and it’s already begun. So I hope that a cyclist would never look at this as a as a green light to blow through traffic lights or stop signs that That’s not at all what this is not what it’s there to do. It’s there to keep people that are trying to do the right thing a little bit safer while they’re doing it. And for both drivers and cyclists, because at the end of the day, we’re all there together. And we just want to have a safe, safe journey and enjoy the ride.

Carlton Reid 52:26

Yeah, hallelujah to that. Jake, thank you ever so much for for talking with us today. Give us a shout out for your for your website. Where can where can people find more information on this technology?

Jake Sigal 52:36

Yeah, great. So you can check us out at Tomesoftware.com and we have a bicycle vehicle page. I’d also would encourage you to like or follow our Tome Software account on LinkedIn. If you’re in the industry, and you look for information, we’ll talk to you but we have some white papers published. And there’s also an email list to stay updated on on some of our upcoming news announcements and things. So really excited to talk about this. And you know, this is personal for me around bike safety, and we’re very proud of the team has been just fantastic to work with on our side, as well as all the cycling car companies, scooter companies, it’s it’s just great seeing everybody come together. So check us out online and really appreciate you putting this together.

Carlton Reid 53:20

Thanks to Jake Sigal of Tome Software but before we transfer across to Peter Norton here’s my co-host David Bernstein with a commercial interlude.

David Bernstein 53:31

Hey, Carlton, thanks so much. And it’s it’s always my pleasure to talk about our advertiser. This is a long time loyal advertiser, you all know who I’m talking about? It’s Jenson USA at Jenson usa.com/thespokesmen. I’ve been telling you for years now years, that Jenson is the place where you can get a great selection of every kind of product that you need for your cycling lifestyle at amazing prices and what really sets them apart. Because of course, there’s lots of online retailers out there. But what really sets them apart is their unbelievable support. When you call and you’ve got a question about something, you’ll end up talking to one of their gear advisors and these are cyclists. I’ve been there I’ve seen it. These are folks who who ride their bikes to and from work. These are folks who ride at lunch who go out on group rides after work because they just enjoy cycling so much. And and so you know that when you call, you’ll be talking to somebody who has knowledge of the products that you’re calling about. If you’re looking for a new bike, whether it’s a mountain bike, a road bike, a gravel bike, a fat bike, what are you looking for? Go ahead and check them out. Jenson USA, they are the place where you will find everything you need for your cycling lifestyle. It’s Jensenusa.com/thespokesmen. We thank them so much for their support. And we thank you for supporting Jenson USA. All right, Carlton, let’s get back to the show.

Carlton Reid 54:57

Thanks David and we’re back with episode 259 of the Spokesmen cycling podcast. Earlier in the episode we had the technology half of the show, now here’s the history half with Peter Norton, the associate professor of history in the Department of Engineering and Society at the University of Virginia, USA.

Carlton Reid 55:20

Peter, autonomous vehicles, they get rid of the driver, that’s fantastic. And by all sorts of 360 degree vision tech and sensors, they can see around corners, so isn’t that surely better than being on the roads with drivers who we know, often distracted, often on, on high and all sorts of things, and aren’t really paying attention. Computers pay attention, Peter.

Peter Norton 55:50

Computers are amazing, they never lose attention. They don’t mean, apart from any sort of processing delay, they may have. They can pay attention, 360 degrees around them, they don’t get tired, they don’t get distracted. They don’t, they’re not emotional. So they have enormous advantages. And a lot of the tech people are very quick to point all of those out to you and conclude right away, well, this makes them better than a human driver. But on the other hand, they have a lot of disadvantages compared to human drivers that the tech sales force tends to ignore. In other words, they add up all the benefits, and then don’t subtract all the disadvantages. And the disadvantages are major. In particular, the sensors and the processing systems that the data go through, generally are very poor at telling what they’re looking at, they’re very good at identifying the likely predictable things like the car in front of you, the car beside you, the limits of the road. But they’re very poor at detecting unusual objects. This is what people are good at. They have a very hard time figuring out what they’re looking at when there’s a bicycle right in front of them. And while they’re trying to figure out what they’re looking at, they have to decide do we do we brake automatically? Do we steer automatically, but if if their confidence on that is low, then you in the in the in the vehicle are going to have a bad experience with this car braking and turning unnecessarily constantly.

Carlton Reid 57:40

So that’s the level five, the fully autonomous system. So that’s that’s, you know, as we know, it’s always five years away. Whenever tech talks about it, it’s two years away. But generally, no matter where we have been in history, it’s always five years away. But there is an awful lot of tech on cars at the moment. So this this tech is out there. This is not in the future. This is this is now. So isn’t it good that human drivers are? As you said, sometimes not as as fantastic as you like, isn’t that good to give them supplementary information supplementary guidance.

Peter Norton 58:22

There’s no question that it can be useful to have some supplementary information when you’re the driver. There’s a couple of important questions that that raises up though. One is, are you going to get the supplementary information you need for example, if it’s a bicyclist and the vehicle has a hard time detecting that it’s a bicyclist Are you going to find out in time that this is a bicyclist. And even I think more important consideration is anytime you supplement automated attention with to human attention, you don’t get the sum of those two, you know, one unit of human attention plus one unit of automated attention does not equal two units of attention. And the reason is human beings are cognitive misers. They want to limit unnecessary effort. And the tech is telling them that they can the tech is saying you may be a little sleepy, but that’s okay. The tech is here watching out. So you don’t have to pull over and take a rest. This is an old phenomenon that goes back long before digital automation where anything the engineers do to make the road safer the benefit is offset, to some extent at least, by human beings; turning that safety benefit into a convenience benefit. And the tech really can ramp up that effect drastically. In fact, you can, as people will listening to this may know, you can go to YouTube and watch videos of people driving their Tesla’s with autopilot, sleeping playing games sitting in the back seat in these are extreme cases that are indicative of a much bigger problem that affects to some degree all drivers.

Carlton Reid 1:00:27

If bikes are going to be equipped with beacons so so whatever kind of beacons they are, whether it’s the phone that you’ve got on you, whether it’s you know, a little tag that you’ve put on, or whether it’s, you know, tech that goes in helmets, tech that goes in bike lights, or is even embedded on the bike, however, the tech is is done, or if autonomous or semi autonomous systems are going to recognise cyclist in some other way. How reliable would all of this have to be, for it to prove to be at least as safe as today’s humans only system?

Peter Norton 1:01:12

This is a very good question. So I mean, there’s a lot of possibilities here. If we have bikes equipped with devices, some kind of transponder that the vehicles around them can pick up. And these vehicles have some kind of odd automated driving systems in them, then the vehicles can, you know, to be much more reliable at detecting them and and taking appropriate action. However, the minute you introduce this possibility, you kind of have to either have an all or nothing situation. In other words, if you don’t have 99%, something like that of the bicyclist equipped, then those that are unequipped are actually at greater risk. And the ones that are at greater risk could I mean, besides the fact that we care about them as individuals, this will also diminish the the overall safety benefit. So then the tricky question becomes do you require cyclists to have this equipment and if so does this start off with say, all new bicycles must be equipped, then of course, you’re leaving out a really decades worth of bikes. My own bike is over a decade old, that are going to be unequipped for years ahead, as soon as drivers have some confidence that cyclists are equipped, their behaviour will change this to the extent that the change depends on the driver, their awareness of the tech and their own safety calculations. So we know already that when a driver sees a cyclist with a helmet on, they’ll pass them by a smaller margin. If a driver sees a cyclist with a child seat on the bike, they’ll pass it by a greater margin. These are behavioural effects. They’re generally entirely unconscious or almost entirely unconscious. And once drivers think that cyclists are equipped with beacons or transponders that their cars are automatically adapting for, we will see the same kind of behavioural consequences. In other words, drivers on average, will give cyclists a smaller margin. And if we have a situation in which actually, not all cyclists have these this equipment, whether it’s 50% or 90%, then you’re going to have some cyclists at least who are exposed to a greater risk thanks to this tech than they would otherwise face.

Carlton Reid 1:03:55

I’ve been speaking to Tome Software and they’ve said yes, it chances are it won’t be beacons, it won’t be transponder tech, it will be, you know, cyclists and pedestrians. The phraseology, as you know, is VRUs, vulnerable road users. They’ll be spotted without any form of technology. So how likely is that and, well, doesn’t that then answer your issues?

Peter Norton 1:04:18

Well, I have a hard time picturing how we get automated driving systems, forgetting about levels of autonomy, just basic automated driving systems that reliably detect bicycles that are not equipped with anything. Just because we know from the research that detecting cyclists is one of the hardest things that autonomous vehicle developers and automated driving systems developers have had to face. So I don’t see how these systems protect bicyclists. And I think they may indeed increase the risk for cyclists because if they give drivers the message that the car is watching out for the cyclists for them, but the car is actually not doing that particularly well then we actually make the situation for cyclists more dangerous, not less dangerous.

Carlton Reid 1:05:15

But if you’re Trek, and their micro brand Bontrager, if you’re Cannondale, if you’re all of these, you know, high end brands, or you’re Garmin, and you’re going to equip, because they’ve got the Garmin, they’ve got like radar cameras in some of them right now. So if you’re going to equip the cyclists, the rich, in effect, the rich cyclist of the future with this kind of tech, well, they’re going to they’re going to do that. Why wouldn’t Cannondale and Trek, you know, produce this tech because they produce and they’re already advocate for, for instance, you know, daylight running LED lights, they all really advocated that advocate made that advocate for helmets. So come bike companies want to sell more things, they will sell more things, if cyclists survive into old age, because they’ll be able to sell them bikes for forever. So bike companies are going to be doing this aren’t they?

Peter Norton 1:06:18

I assume they will. I mean, this depends in part on what the tech really proves it can do and whether cyclists are convinced that it does deliver these promised benefits. But let’s assume that the tech does work fairly well, then certainly there are going to be some cyclists who want it. If it’s fairly expensive, as I think probably will have to be, then not all cyclists will have it. Already we have a situation. And I think it’s it’s what we would naturally expect, where cyclists have different risk calculations and different budgets and arrive at different conclusions about how much protection they want. Do they want a helmet? If so, what kind do they want hive is? Do they want lights? You know, a lot of times the calculation is a convenience calculation. My bike is not, does not have lights right now, but it’s dark, but it’s a short ride, I’ll take the chance, I’ll just be careful. These are normal human risk calculations. And I think the tech will become a part of that normal risk calculation. Now it gets complicated, of course, when systems get designed around assumptions, such as whether a cyclist has certain equipment or not, whether cars have certain capabilities or not. And if we have cyclists who are equipped, and we have road design decisions, and driver decisions that respond to the assumption that we have cyclists who are equipped, then we’re changing really what begins as an individual choice by an individual cyclist to get the high end bike with the high end safety tech. And we’re now involving the other cyclists who have an older bike who have a budget. And their safety exposure has changed through no action of their own. Because road networks, traffic cycling are all components of complex systems. And no individual action within a complex system is taken in perfect isolation.

Carlton Reid 1:08:38

But Peter, I’m safe. Who cares about everybody else? I’m, I am on a $5,000 Super Deluxe, fantastic roadmachine. I’ve also paid $1,000 for the latest in bicyclist detection. I’m saved, who cares about anybody else? What is the problem with that?

Peter Norton 1:09:02

Well, I don’t think I have any objection to an individual cyclist who wants to put out the money for this this high tech safety equipment, that’s fine at an as an individual choice. What concerns me is the systemic effects. And I’m not making the individual cyclist here responsible for those because now we’re talking about policy. We’re talking about law. We’re talking about engineering standards. Could you know things like lane widths, how you separate bike lanes, if at all from traffic. And it’s at that level that that kind of tech has some serious implications, implications that the individual cyclist who has a big budget, I know may not be their concern. And I don’t have a quarrel with that. But it is a concern of the society that we live in and the people who make the decisions about that society. So for example, if the tech turns out to actually make cyclist cycling safer for those who have it, but more dangerous for those who don’t, does that become grounds in policy for requiring all cyclists to have the necessary equipment for cars to detect them? If that does, then we now have problems about access to cycling among those with budgets, or deterring cycling in a society where we need more, not less for lots of reasons, including sustainability and public health. So these are where these these developments become problematic. We are not protecting these unequipped cyclist when we have equipped cyclists, and we are in to some degree making their situation more serious as drivers come to expect cyclists to be equipped. And eventually even road designers. Road authorities start to assume that cyclists should be equipped, perhaps even the law may begin to expect this such that, you know, an injured party in a courtroom may have a weaker case, legally, if they didn’t have this tech that, you know, nobody had just a few years earlier. This is not speculation. We’ve seen this with bicycle helmets where once the bicycle helmets are out there, some authorities have decided that all cyclists must have them. And there have been court cases where the cyclist who was one who did not have a helmet was at a disadvantage after an injury because of not having a helmet that could take on a new life with the safety tech that we’re talking about.

Carlton Reid 1:12:02

You’re talking from a like a dystopian point of view, basically, historian, and you’ve seen this happen, though your your dystopia is based on what actually has happened in history?

Peter Norton 1:12:17

Oh, yes. Yeah, you know, experience is your best teacher in history is just a sort of systemic study of human experience and the lessons that come from it. I mean, the most elementary lesson about road safety from history is that safety is not some linear measure that is neutral in its relationship with people. Safety is always: safety for whom? Safety is always a question of priority. Safety is always a question of recognition. So there’s there’s a sort of official favour that safety confers but also sort of unofficial recognition. If a say a pedestrian is in a roadway, in conflict with the travel path of a motor vehicle it appears obvious from our early 21st century point of view that the pedestrian has it as a task, and that is to get out of the way. That’s a point of view that did not exist a century ago, when when the prevailing notion was exactly the opposite. And so this means we can’t talk about safety without talking about power without talking about priority without talking about the inequality really between categories of road users. I heard you use the term vulnerable road user a few minutes ago. And the term connotes a road user who is in some way less than optimal as a road user. But we could have a different vocabulary where we have road users, like pedestrians, like cyclists, and then we have dangerous road users or DRUs. Why is it that we have VRUs but not DRUs? These are all questions that history can help us be alert to and it’s really worth being alert to them because, you know, for a lot of reasons, number one being climate change. We are overdue for a rethink about how we’ve chosen these priorities and who we should favour in these conflicts.

Carlton Reid 1:14:44

So, priority and prioritising. I do hate using the term, absolutely, it’s an ugly term VRUs prioritising pedestrians and cyclists with that actually, if that has And say we live in a perfect world. And that happened. The oldest tech actually prioritised cyclists and pedestrians. That’s that’s that’s the beautiful thing where we’re holding out for Peter. If that happened, would that then make it incredibly hard to sell cars to people? Because we’re going to be prioritising these people who have never been prioritised before?

Peter Norton 1:15:21

The answer is definitely yes. And I can say definitely, because we had that dilemma before. We had that dilemma when the question of who do we prioritise between motor vehicles and pedestrians first arose over a century ago? And the answer was, if you prioritise pedestrians, as was universal over a century ago, then drivers’ driving experience is diminished, you can’t go fast, you have to yield frequently. And certainly the driver’s experience is worse. Now, their experience as human beings may not be worse, because in such a world, they may find that actually, they don’t have to drive as much. So a driver is not existentially a driver who can be nothing else. Every driver is a potential pedestrian or transit user or cyclist. And so maybe not everywhere, maybe only in some places, maybe only in cities or relatively dense areas. And maybe not even on all streets in such areas. We can reimagine what streets are for I think it’s worth doing because we have to find some way to have a sustainable future. That’s going to require less driving. And I think that, while that may sound scary in a car dependent world can look attractive in a less car dependent world. I mean, frankly, it’s a lot like how not smoking sounds scary when you’re addicted. But it feels liberating once you’ve stopped smoking for a while. So Ah, yes, the answer to your question is yes, it could be a bad experience for drivers if we prioritise pedestrians and cyclists in some areas. Another reason why we don’t have to speculate about that, by the way is that there are places where drivers can drive but are not prioritised. Where streets are shared shared spaces, or streets in the Netherlands, where cars are, are admitted as guests according to the terminology there. And in such shared spaces, people can and do drive. It’s a different experience. It’s not necessarily much worse, depending on you know, how much of a hurry that driver is in. And such techniques don’t have to be used everywhere, but they can be used somewhere. And some places they they can be a beautiful

Peter Norton 1:18:15

possibility that we haven’t seriously considered enough.

Carlton Reid 1:18:19

What would be your advice to bike companies who are looking at this technology? Do you think it’s it’s something they ought to clear off? Or do you think they’re also tech companies and bicycles are tech? Do you think they they are absolutely going to go with this anyway, no matter what somebody like you says, so let’s let’s what what should they be doing?

Peter Norton 1:18:42

Well, I think that’s gonna depend a lot on on the particular markets, there probably are markets these are the markets where the cyclist is still not something drivers expect to see. This is, of course, practically ubiquitous in the USA, but many other countries as well. In such environments, there’s certainly going to be interest in this tech among cyclists, and perhaps even eventually, among road authorities of various kinds. I think cyclists as consumers need to be careful about what they’re being sold. They should be sceptical if they’re, if they’re if the messages that this tech is sort of automatically protecting them. I mean, after all, the overwhelming majority of cars on the road have no means of picking up the tech that may be in the bikes, so they can’t expect drivers to be automatically adjusting through some sort of technological, some sort of signal between the two vehicles. It’s frankly not clear to me what the tech in the bike will do for the cyclist, until the vast majority of cars have the tech on board to adjust accordingly to the cyclists. That’s a piece I don’t really get, I don’t see how we get from the where we are now, where the vast majority of cars would have no means to detect anything in the bike to a world where the cyclists can expect that any car passing them, or approaching them, is detecting the bike automatically. So I don’t know how we get to that point, it may be that I’m even misunderstanding something about how this tech is supposed to work. I’ve been confused by it, in part, because the messages I’ve been getting from the tech companies has been conflicting on this point. But to return your question, should should bike companies do it? Well, yeah, I mean, if, if they’ve got a market that’s interested in paying for this stuff, and the cyclists knows what they’re getting, and is not misled into imagining they’re getting more protection, than it’s worth. Sure, I just have a hard time seeing that the technology can deliver the safety benefit that would be necessary to justify the expense in the bike right now.

Carlton Reid 1:21:28

You’re almost saying that if it was just a transponder that was talking to a driverless car or an equipped human driver car, that’s one thing, but then what’s actually going to cyclists gonna have, and they’re going to have, like, you know, a heads up display to tell him that there’s a threat coming for the variety of ways that this tech can be sold to the cyclist, if it’s going to be just something that keeps cars away from you. Well, that’s one thing. But if it’s all gonna say out, but you can actually see when there’s a car about to run you over, you can jump off the road. That’s also something that’s you know, you need more things on a bike. To do that, you’d have to have a display, you’d have to have haptics telling you look, you know, in 15 seconds is this motorist is going to hit, you’re going to have all this kind of stuff. So it’s you’re making cycling into, you know, Judge Dredd.

Peter Norton 1:22:23

It’s very hard for me to imagine any cyclist — and I’m speaking as one who would have any use for information coming in from some kind of sensor system — that could possibly be anything but a detriment to the sensor system that every cyclist already has, namely, their vision and their hearing. So a cyclist in a busy environment, your vision and your hearing are on high alert. And any sensor system that tries to crowd that high alert, personal sensor system with more data, it’s going to be an annoyance. It can’t tell you much that your senses can’t already more reliably tell you. I mean, you might have some kind of threat map on your handlebar, that tells you what’s up ahead. But the attention you’d have to give to that screen would be a distraction in itself. And the reliability of what it was showing you would have to be very poor, because this would be real time data coming in from perhaps actively transmitting vehicles as well as whatever the sensor system on the bike is picking up. I can’t imagine a voice or haptic system or audio signals or visual signals that would be reliable enough and relevant enough to a cyclist in a busy environment to be anything but a nuisance.

Carlton Reid 1:24:04